|

The Western Railway Museum is selling BART Legacy Fleet Train Operator Consoles sourced from retired cars. For $1000 each, you can own a core piece of BART history and support the preservation of three complete legacy cars at the Museum.

This video presents a history of the different train operator consoles of the Legacy Fleet, the functions of the console, and how to purchase one from the Museum if so inclined.

0 Comments

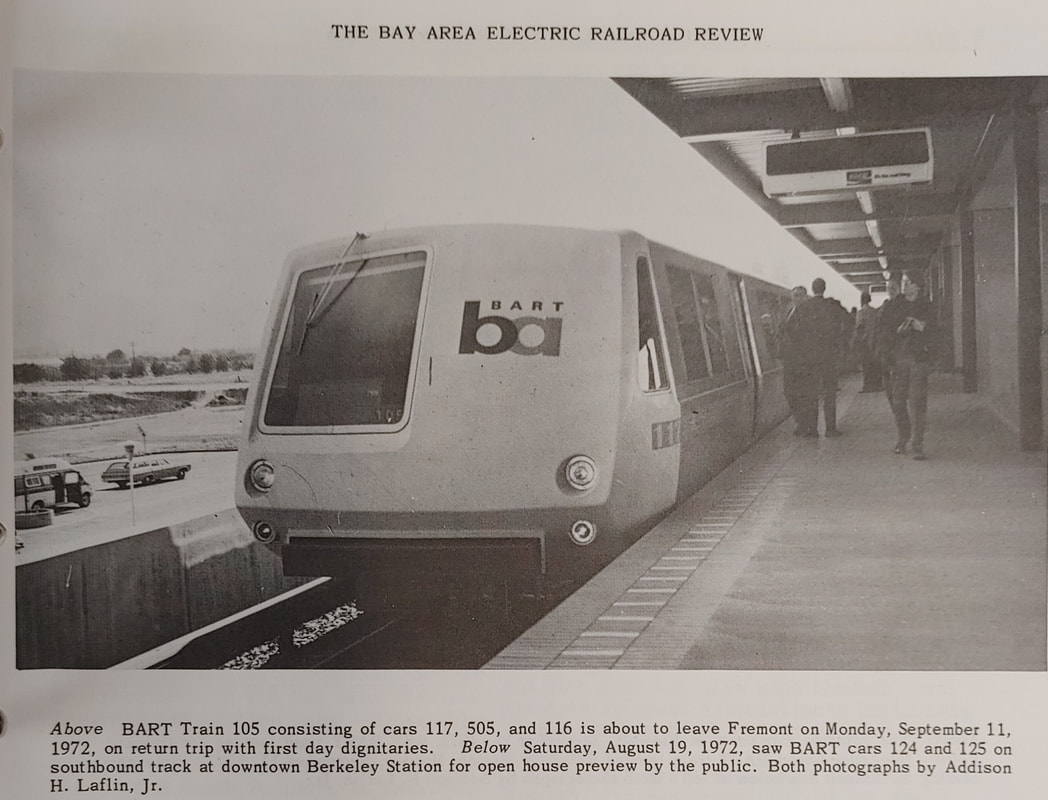

B2 Car 1806 is, on first look, just any old B car. It runs in the middle of trains, and seats 53 people. It has a few smells and a few bulbs are out. Underneath all that, B2 car 1806 is one of many historic BART cars. The 1806 was originally built by Rohr as A car 117. It was among the first two dozen BART legacy cars built. It was built in Chula Vista, CA, and delivered to BART's Hayward Yard on 5/16/1972. It was used for pre-revenue testing of the BART system, and entered service on BART's opening day, Septmeber 11, 1972. By the 1980s, many A cars were worn out and/or damaged. BART was a new railroad and in some ways, still learning the ropes - there are accounts of runaway cars, collisions, and fire damage during these early days. Car 117, alongside 34 other A cars, were destined to become B cars. The unique design of the A cars facilitated such conversion (which was miles cheaper and faster than building new B cars). A car 117 became B car 806 in about late 1980. The "new" 806 rolled in service until its midlife refurbishment in 2001. As a product of the refurbishment, B car 806 became B2 car 1806. The 1806 is still in service, far beyond the original intention of its designers. This old car will probably be scrapped this year or next year, but if anything, it has carried the millions through thick and thin for over 50 years.

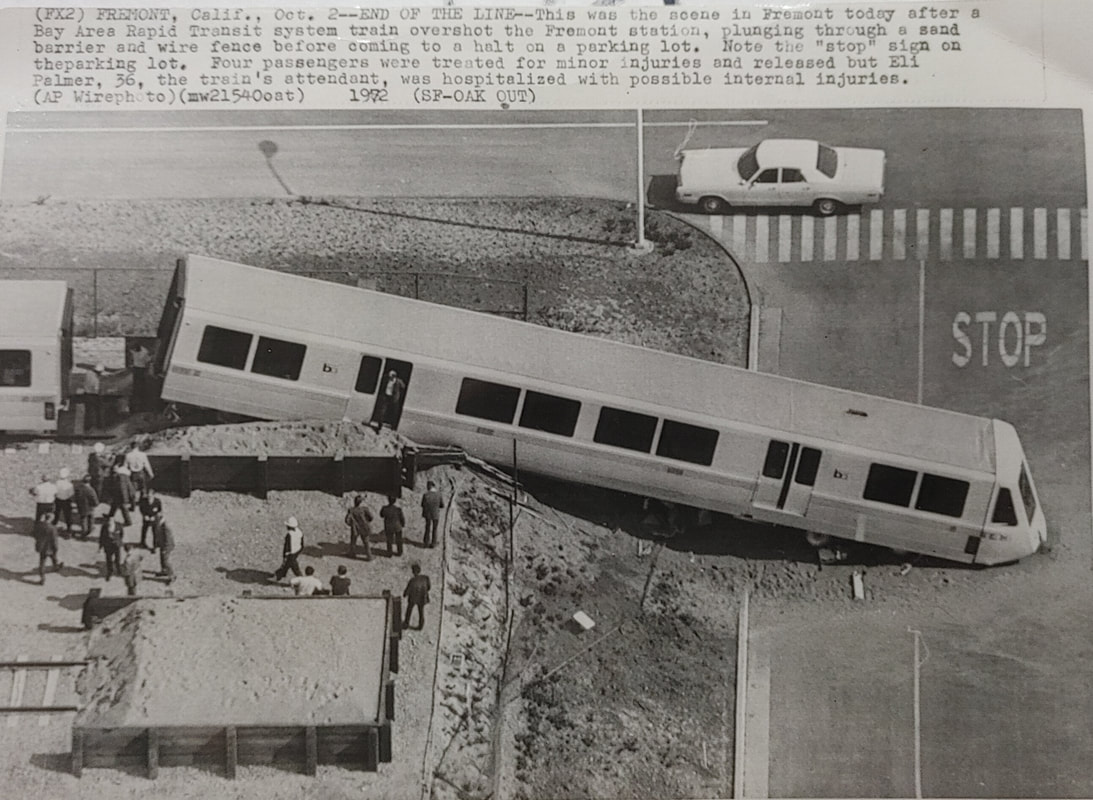

Today marks the final chapter of one of BART’s most historic Legacy Cars: the Fremont Flyer. The Fremont Flyer was originally known as A car 143, the 48th car off of the Rohr assembly line in Chula Vista, CA. The car was delivered to Hayward Yard on August 31, 1972, less than two weeks ahead of BART’s opening day, and underwent testing to ensure the car was ready for revenue service – or so it was thought. The shiny new 143 entered revenue service on October 2, 1972, filling in for two broken down trains. Dispatched as Train 307, a short two car train with A cars 143 and A car 118 – the latter was a “Day One veteran” – headed south from Hayward Yard to Fremont station (143 leading), thence to MacArthur (118 leading), the northern terminus at the time. Train 307 then headed south to Fremont. While approaching the A85 interlocking just north of Fremont station, the train received a 27-mph speed code – one of eight discreet speed codes on the BART ATC system – to ensure the train would safely cross over from track 1 to track 2 and stop within the platform. Unbeknownst to anyone on the train, a tiny yet faulty crystal, controlling an oscillator on a printed circuit board, incorrectly decoded the speed code to mean the train should speed up to almost 70 mph – which it achieved. Crossing over the A85 interlocking at 66 mph, the train attendant recognized something was amiss and did all that was possible to stop the train (including pressing the stop button so hard he broke the mounting and pushed it through the console). Even then, the braking was inadequate; the train sped through the center of platform 2 at 42-50 mph and impacted the sandpile at about 26-33 mph (sources debate speeds), continued and landed in the parking lot – short of a stop sign. Injured riders and the train attendant were rushed to the nearby Washington Hospital. The accident brought national attention to the safety of BART, alongside significant changes to carborne ATC equipment and changes across the system. Such changes included, but were not limited to, additional circuitry to ensure the decoding of the correct speed code, alongside the addition of wayside markers showing where a train should start braking and the maximum speed. Years of revisions and refinement to the ATC system following the Fremont Flyer incident has made BART a safer system for all who ride it. A car 143 never carried another paying rider but it found a new life as a B car. In fact, the damage was severe enough for the BART forces to recommend salvaging parts and scrapping the car. Fortunately, BART engineering know-how was on its side and the 143 was repairs and converted into B car 826 by Hayward Shop forces by the end of 1981. It then rolled again, this time as a standard B car for about 20 years. As part of the A and B car refurbishment of the A and B cars during the turn of the century, B car 826 was rebuilt and renumbered into B2 car 1826. In its final years, it was assigned to Concord yard and seen in the middle of long Yellow line trains. After this major incident, but then a successful repair and conversion, old 143 carried thousands of passengers millions of miles. BART is currently replacing their Legacy Cars with the Fleet of the Future cars. The Fremont Flyer was no exception to this, and after 50 years since it first entered revenue service, this car was decommissioned. BART forces also recognized the historical importance of this car, and invited Western Railway Museum volunteers to preserve artifacts from this car for posterity and for use in the future Rapid Transit History Center. WRM volunteers were able to identify the Y end (once cab end) exterior and interior number plates, the ADtranz rebuilding plate (c. 2001), and a seat. These artifacts will help tell us tell the story of one of the most historic transit vehicles of the BART legacy fleet. This article was written by ATP Transit for the Western Railway Museum.

AN: Harre Demoro (1939-1993) was the Tribune’s reporter on BART construction for a decade and a half, from groundbreaking to the 1970s. His work is imbedded throughout this site. It appears the years of BART delays and unreliability worn into him through the end of the 1970s and 1980s. As much as he was a supporter in the 1960s, he was a critic in the early 1980s. Many times, his criticism was valid as much as it was then as it is today. If he was alive today, he would likely be aghast at the crime, dirtiness, and other “quality-of-life” conditions (alongside reliability and BART still being unable to “run the system like they promised”), but perhaps most supportive of the Legacy Fleet reaching 50 years of service.

The following essay was published in the February 1980 issue of Pacific News, under the Column “Out West.” Demoro writes: It is common for electric rail rapid transit cars to outlive their usefulness, to continue to run long after they have become obsolete. The East Boston subway cars built in 1923-24 by Pullman, are just now being phased out. Most Philadelphia Broad Street cars are past forty years of age. New York, the toughest subway town in the world, obtains thirty to forty years of life from its cars. The situation is different in the San Francisco area, where planners for B A RT - the Bay Area Rapid Transit system - are busily drafting plans and specifications for at least two hundred proposed new rapid transit cars that will cost $ 1 million each and, with luck, would go into service in 1985 [A/N: The C1 cars, as they are known now, entered service on 3/28/1988]. We might recall that B A RT did not open its first line until 1 972, and that except for a few cars rebuilt from the prototypes delivered in 1 970, there is not a BART car in 1980 that is even ten years old. The 450 cars built by Rohr Industries were expected to last at least thirty years, but it now seems clear a significant number of them will be gone before they are fifteen years old. Some have already been scrapped due to wrecks and fires. Having covered B A RT as a newspaperman from 1962- 1 977, watching the engineers and bureaucrats plan, design, build and operate the system, I might be expected to be surprised at the short lifespan of the rail cars. But when I look back, I realize I should not be. The car reflects almost none of the experience gathered by the electric railway industry during seventy years prior to the BART design effort. Too much attention was paid to innovation. Some history: The last major electric railway design effort was the Electric Railway President's Conference Committee, which produced PCC streetcars, such as those in San Francisco (PACIFIC NEWS, November, 1979), and the PCC rapid transit car, still in use in Boston, Cleveland and Chicago. That program died in 1952 for streetcars, and about a decade later for rapid transit, with Chicago and Boston carrying on the final research. By the time BART was in detailed design, the platoons of experts who knew something about subway car design were either retired, deceased or happily employed on the other rail systems. There was an undisguised snobbery among BART engineers who held that the past was not worth considering, and that modern methods, such as computers and aerospace technology, would be sufficient. It is true that many of the innovations BART attempted had merit. The 1000-volt DC power system was modern and on paper was the electrical network needed to propel the high-performance trains. The solid-state chopper system that feeds electricity to the traction motors was a necessary improvement, both for the high performance required and for its ability to react instantly to the automated control system. But as we now know, the chopper control and motors are erratic, the 1000-volt power system had to be extensively modified - and the cars are getting shabbier and, to this rider, noisier and looser, by the minute. If the cars had been reliable, the awkward arrangement of having end cab (or A) cars with controls, and mid train (or B cars) without controls, would have proven successful. On a system as unreliable as BART, one component failure takes the entire train to the yard. On a real subway, with all cars alike, the defective car can be switched out of a train at a siding called a pocket track, and the remaining cars continue in service. BART, unfortunately, only has three pocket tracks. The new cars, I am told, will have flat ends with doors. One may assume that with a flat end the car with controls can be put in the middle of the train in an emergency. At long last a design that is aimed at getting passengers home, rather than one pleasing engineers who like to tinker, may be assured for BART. The new cars are to have control cabs at one end and will replace most or all of the slant-end cab cars now in use. The present cab cars that appear to have a few miles left on their aluminum shells are to be rebuilt as midtrain, or B cars. BART already is cutting the noses off of some of the worn-out cab cars and making them B cars. Ultimately, the present cars will be more fire-resistant. Perhaps by 1985, thirteen years after the system opened to the public, BART may begin to operate like other rail systems. The fact that these others, including new subways in Washington, D. C. and Atlanta, have a car design that is practical, should be a lesson to the BART designers. |

About

"The Two Bagger" is meant to be a place to store more "blog" style posts on various cars, pictures, and random tidbits/trivia. At BART, a "two bagger" is a rather informal name for a two car train. Two car trains rolled in revenue service back in 1972. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed