A History of the BART Legacy Fleet

Selections from Legacy Fleet: The Story of BART’s Old Cars and The BARTchives, by ATP Transit, 2022

Setting the Stage: The Laboratory Cars

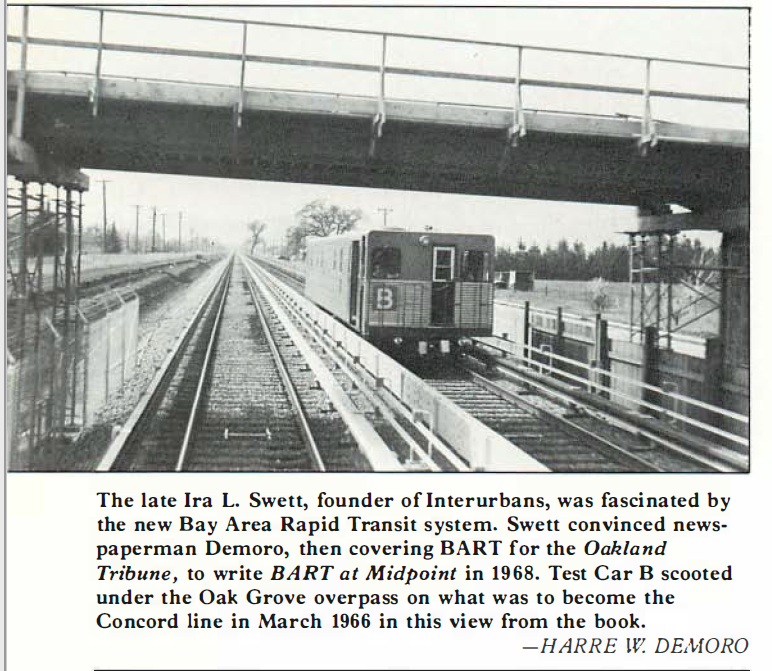

BART’s first electrically powered railcars were fluted metal boxes designed for operation on the 4.4 mile Diablo Test Track in central Contra Costa County. The three cars, lettered A, B, and C, were publically nicknamed “Agnes,” “Betsy,” and “Clara” respectively. All three cars were built by the Budd Company, and assembled by the Western Pacific shops in Sacramento.

For three years, various types of trucks, wheels, propulsion systems, brake systems, couplers, gear boxes, ATC systems, and current collectors were evaluated on the three cars. Data from these laboratory cars were used to write the specifications for the eventual revenue BART fleet.

Following the conclusion of the Diablo Test Track demonstration project, the Laboratory cars found a second life as the first full-sized electric railcars to test the (soon to be) revenue BART system, and were seen rolling between Oakland and Hayward in 1970.

For three years, various types of trucks, wheels, propulsion systems, brake systems, couplers, gear boxes, ATC systems, and current collectors were evaluated on the three cars. Data from these laboratory cars were used to write the specifications for the eventual revenue BART fleet.

Following the conclusion of the Diablo Test Track demonstration project, the Laboratory cars found a second life as the first full-sized electric railcars to test the (soon to be) revenue BART system, and were seen rolling between Oakland and Hayward in 1970.

Designing the BART Car

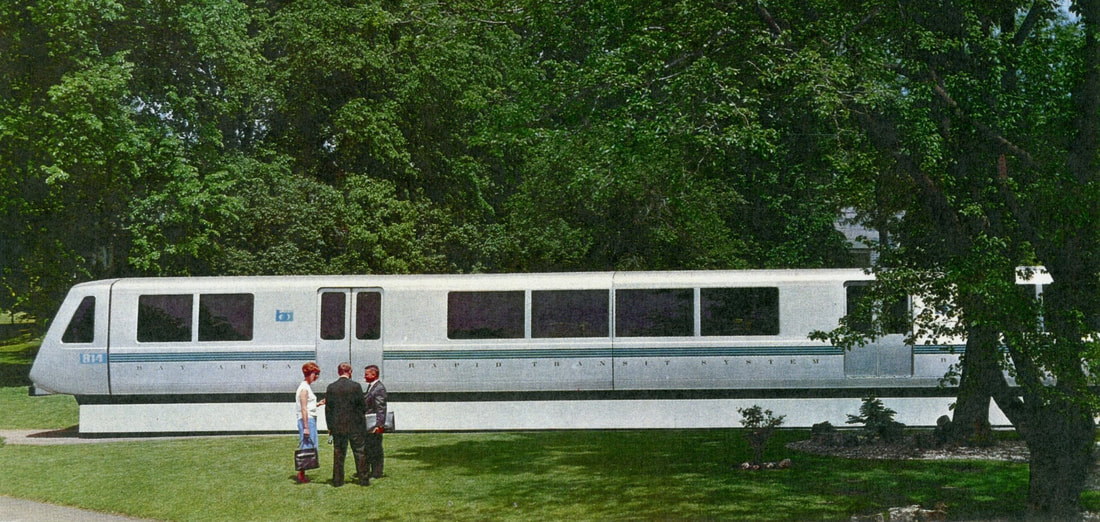

Starting with the overall objectives and constraints for the BART system, Sundberg-Ferar Industrial Design of Detroit, and St Louis Car Division of General Steel Industries of Granite City, IL, designed the aesthetic and human engineering aspects of the BART vehicle. The design of the mockup, undertaken by Sundberg-Ferar, was the product of many rounds of renderings, models, and collaboration with car builders. This cycle of collaboration between all parties allowed for a more seamless connection to the construction of the actual revenue cars. The car itself was manufactured by W. Ashley Gray Jr. of St Louis Car Division of General Steel Industries, for a cost of $400,000.

The mockup of the BART car was numbered 814 after the original district offices at 814 Mission Street, San Francisco.

As noted during the unveiling of the car at the Diablo Test Track on June 22, 1964, the BART car was to represent the best of BART, and functions as a symbol of the entire BART project. As said by General Manager B.R. Stokes:

This design car epitomizes more than anything else our goal of providing the most comfortable, fastest, safest and most economical means of interurban transportation the world has ever known.

Our entire purpose in life, our only reason for existence, is to produce a system so inviting that Bay Area travelers will choose to ride the 80 mile-an-hour trains instead of adding to the traffic congestion that has had such an undesirable effect on our urban way of life…

The car we have unveiled here today is destined to establish an exciting new trend in rapid transit conveyances…This is not just a warmed over version of an existing commuter train. It's entirely new - the first in over a quarter of a century. There's nothing to compare it with for comfort and luxury, except possibly a jet airliner or the most expensive automobile.

Designer Carl Sundberg explained the design process of the car. The following is a transcription from his own words:

…Situated as we are in the heart of the automobile industry, our people are vitally aware of the importance of good vehicle design. We tried to employ the talent and knowledge we have gained here to produce for the Bay Area people a design that transcends anything yet conceived in the field. For us, it was labor of love.

We began the design process with the most essential ingredient, the human being, tailoring all elements to his or her needs. We knew, also, that the people of the Bay Area traditionally accept newness, that they do, in fact, hunger for innovation.

We gave the nose a sophisticated, sculptured look, yet we kept it simple; we used no gimmicks or clichés strictly for the sake of appearance. We wanted a modern vehicle, yet we stuck to the contention that a rapid transit train should look like a rapid transit train, and nothing else.

We wanted the car to appeal to all ages and walks of life, so we gave it a fleet look to reach the younger generation, yet a solid, practical, even dignified look to appeal to adults.

It was our purpose to make the interior of the car, as well as the exterior, competitive in design and comfort features with the most expensive automobile.

This, I feel, we have done.

The 1.10 car mockup was displayed across the San Francisco Bay Area before the opening of the system. Hundreds of thousands of future riders provided their comments to help shape the human element of the BART railcar. The mockup also trekked down to Los Angeles, to help drum up support for a heavy rail system in their vicinity. In December 1971, car 814 was sold to Atlanta for the planned MARTA system, for a sum of $1,000.

By May 1990, the 814 made its way to the Gold Coast Railroad Museum in Miami, Florida. It’s assumed to have been a victim of Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

The mockup of the BART car was numbered 814 after the original district offices at 814 Mission Street, San Francisco.

As noted during the unveiling of the car at the Diablo Test Track on June 22, 1964, the BART car was to represent the best of BART, and functions as a symbol of the entire BART project. As said by General Manager B.R. Stokes:

This design car epitomizes more than anything else our goal of providing the most comfortable, fastest, safest and most economical means of interurban transportation the world has ever known.

Our entire purpose in life, our only reason for existence, is to produce a system so inviting that Bay Area travelers will choose to ride the 80 mile-an-hour trains instead of adding to the traffic congestion that has had such an undesirable effect on our urban way of life…

The car we have unveiled here today is destined to establish an exciting new trend in rapid transit conveyances…This is not just a warmed over version of an existing commuter train. It's entirely new - the first in over a quarter of a century. There's nothing to compare it with for comfort and luxury, except possibly a jet airliner or the most expensive automobile.

Designer Carl Sundberg explained the design process of the car. The following is a transcription from his own words:

…Situated as we are in the heart of the automobile industry, our people are vitally aware of the importance of good vehicle design. We tried to employ the talent and knowledge we have gained here to produce for the Bay Area people a design that transcends anything yet conceived in the field. For us, it was labor of love.

We began the design process with the most essential ingredient, the human being, tailoring all elements to his or her needs. We knew, also, that the people of the Bay Area traditionally accept newness, that they do, in fact, hunger for innovation.

We gave the nose a sophisticated, sculptured look, yet we kept it simple; we used no gimmicks or clichés strictly for the sake of appearance. We wanted a modern vehicle, yet we stuck to the contention that a rapid transit train should look like a rapid transit train, and nothing else.

We wanted the car to appeal to all ages and walks of life, so we gave it a fleet look to reach the younger generation, yet a solid, practical, even dignified look to appeal to adults.

It was our purpose to make the interior of the car, as well as the exterior, competitive in design and comfort features with the most expensive automobile.

This, I feel, we have done.

The 1.10 car mockup was displayed across the San Francisco Bay Area before the opening of the system. Hundreds of thousands of future riders provided their comments to help shape the human element of the BART railcar. The mockup also trekked down to Los Angeles, to help drum up support for a heavy rail system in their vicinity. In December 1971, car 814 was sold to Atlanta for the planned MARTA system, for a sum of $1,000.

By May 1990, the 814 made its way to the Gold Coast Railroad Museum in Miami, Florida. It’s assumed to have been a victim of Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

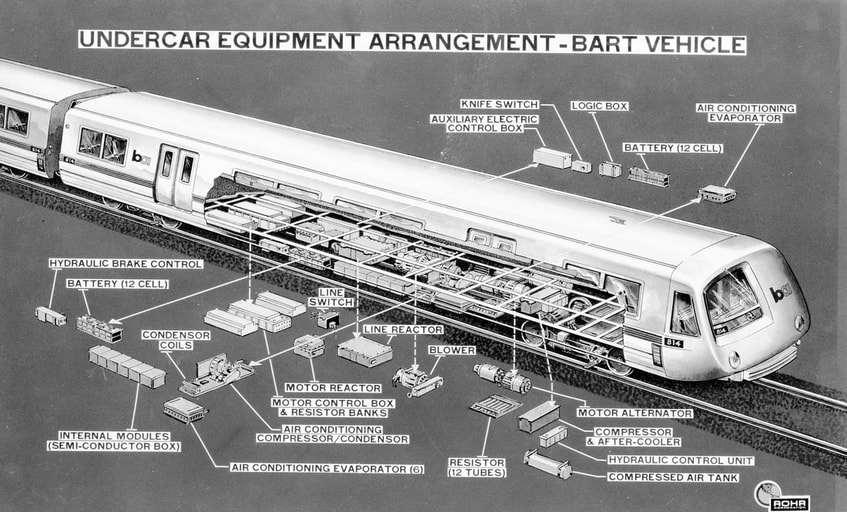

On the technical side, the BART car was designed to be the most advanced rapid transit car ever built.

The automatic train control (ATC) system was designed to run trains at speeds up to 80 mph between stations, and bring them to a stop with the precision of plus or minus six inches. BART was the first rapid system to have the merging of multiple lines under ATC.

The car was built using extruded aluminum, contrasting to traditional sheet metal construction. These extruded aluminum pieces were combined to form a monocoque body shell. Although a rather new process for rail transit, these were proven techniques for the aerospace and aircraft industries.

All matters of truck design were considered as part of the Diablo Test Track project. By the time the revenue cars were built, the BART car was equipped with cast steel LFM-Rockwell inboard bearing trucks. The cars were equipped with automatically leveling air bag suspension, in addition to rubber bumpers, for a smooth ride.

The high performance characteristics of BART required a new propulsion system. Taking advantage of recent developments in chopper control and increases in thyristor ratings, the BART car became the first rapid transit car to employ such a system. Hydraulic disk braking was used on the cars, an offshoot of the technology developed for off-highway trucks and aircraft landing gear.

Together, the carbody, sans undercar equipment, weighed about 200 pounds per linear foot. The cab-equipped A car, with all equipment and empty of passengers, weighed approximately 59,000 pounds, while the cabless B car, similarly empty, weighed approximately 57,000 pounds. The respective weights per linear foot of car length (786.6 lb and 814.3 lb respectively) placed the BART cars as among the lightest rapid transit cars ever made.

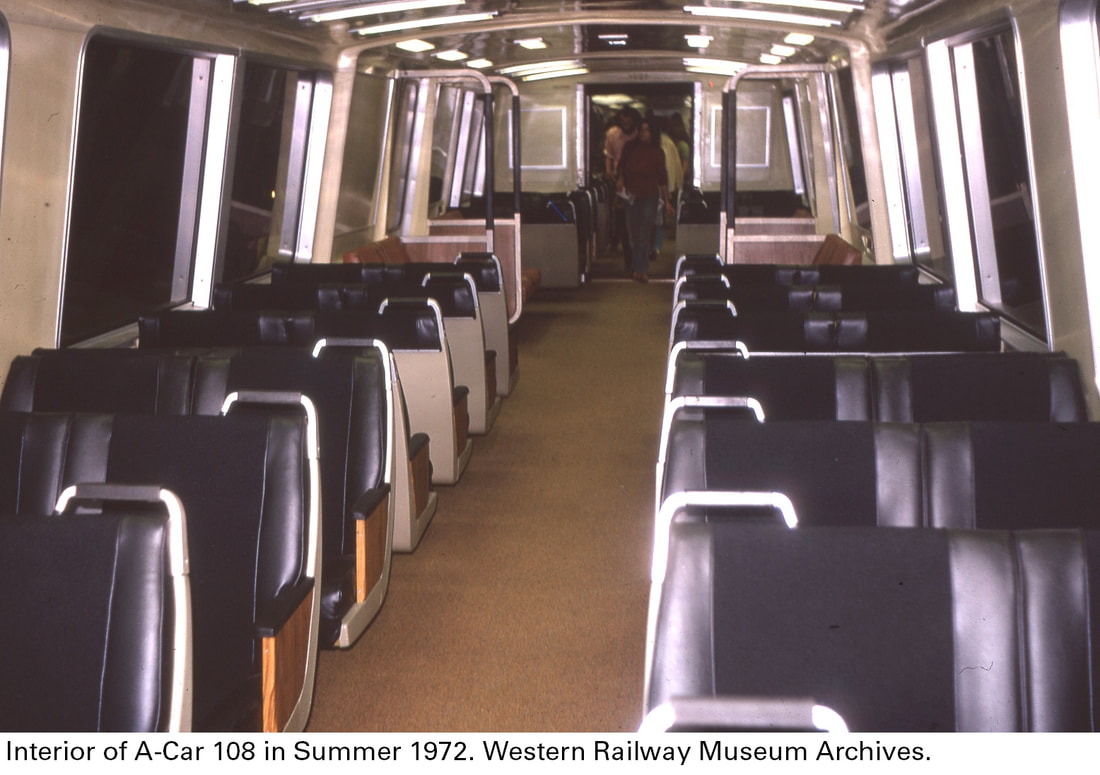

The interior was designed to be relatively comfortable, and early reports firmly state the importance of a clean and pleasing interior for “evening and Sunday trips - to the theater for example – and by ladies in midday for shopping, etc.” The BART car was to have a positive and dignified look, neither extravagant nor draconian, but realistic to both the requirements for the wear and tear related to the operation of a transit system and the goal of competing against the commuter automobile, including the factor of comfort. The large windows, air conditioning, end-to-end carpeting, 72 upholstered seats, modern lighting, and other features all contributed to the idea that the BART car was to be a “public asset and a source of pride.”

In all, the design of the BART car combined both desires to provide a comfortable vehicle and a technologically advanced car in an attractive package. Certain aspects of the car would become industry standard, while other aspects were to be left as BART-only curiosities.

BART cars were divided into two distinct car types – the A car and the B car. A cars had a 5 foot long sloped fiberglass cab, containing train control equipment and space for a “train attendant” (now called “train operator”). They were designed to be used as lead or trailing units in revenue service, and their aerodynamic shape also provided a pleasing appearance. The second type of BART car, the B car, resembled an A car, without a cab. They were designed to be used only in the middle of trains during revenue service, but have hostling panels for manual operation in yards.

Early on, there was a serious consideration to have the cabs as detachable units, mounted on to a car in the yard as needed. In the most extreme case, this would mean that every car would be built as a B car, but with attachment hardware so it could become an A car for the day. This detachable pod concept was not chosen, particularly due to the large savings in having permanently mounted cabs on A cars, alongside the only real benefit of the detachable pod being traced to novelty. However, the design of the A car, with a mounted fiberglass cab, would prove valuable for the A to B car conversions in the coming decades.

The automatic train control (ATC) system was designed to run trains at speeds up to 80 mph between stations, and bring them to a stop with the precision of plus or minus six inches. BART was the first rapid system to have the merging of multiple lines under ATC.

The car was built using extruded aluminum, contrasting to traditional sheet metal construction. These extruded aluminum pieces were combined to form a monocoque body shell. Although a rather new process for rail transit, these were proven techniques for the aerospace and aircraft industries.

All matters of truck design were considered as part of the Diablo Test Track project. By the time the revenue cars were built, the BART car was equipped with cast steel LFM-Rockwell inboard bearing trucks. The cars were equipped with automatically leveling air bag suspension, in addition to rubber bumpers, for a smooth ride.

The high performance characteristics of BART required a new propulsion system. Taking advantage of recent developments in chopper control and increases in thyristor ratings, the BART car became the first rapid transit car to employ such a system. Hydraulic disk braking was used on the cars, an offshoot of the technology developed for off-highway trucks and aircraft landing gear.

Together, the carbody, sans undercar equipment, weighed about 200 pounds per linear foot. The cab-equipped A car, with all equipment and empty of passengers, weighed approximately 59,000 pounds, while the cabless B car, similarly empty, weighed approximately 57,000 pounds. The respective weights per linear foot of car length (786.6 lb and 814.3 lb respectively) placed the BART cars as among the lightest rapid transit cars ever made.

The interior was designed to be relatively comfortable, and early reports firmly state the importance of a clean and pleasing interior for “evening and Sunday trips - to the theater for example – and by ladies in midday for shopping, etc.” The BART car was to have a positive and dignified look, neither extravagant nor draconian, but realistic to both the requirements for the wear and tear related to the operation of a transit system and the goal of competing against the commuter automobile, including the factor of comfort. The large windows, air conditioning, end-to-end carpeting, 72 upholstered seats, modern lighting, and other features all contributed to the idea that the BART car was to be a “public asset and a source of pride.”

In all, the design of the BART car combined both desires to provide a comfortable vehicle and a technologically advanced car in an attractive package. Certain aspects of the car would become industry standard, while other aspects were to be left as BART-only curiosities.

BART cars were divided into two distinct car types – the A car and the B car. A cars had a 5 foot long sloped fiberglass cab, containing train control equipment and space for a “train attendant” (now called “train operator”). They were designed to be used as lead or trailing units in revenue service, and their aerodynamic shape also provided a pleasing appearance. The second type of BART car, the B car, resembled an A car, without a cab. They were designed to be used only in the middle of trains during revenue service, but have hostling panels for manual operation in yards.

Early on, there was a serious consideration to have the cabs as detachable units, mounted on to a car in the yard as needed. In the most extreme case, this would mean that every car would be built as a B car, but with attachment hardware so it could become an A car for the day. This detachable pod concept was not chosen, particularly due to the large savings in having permanently mounted cabs on A cars, alongside the only real benefit of the detachable pod being traced to novelty. However, the design of the A car, with a mounted fiberglass cab, would prove valuable for the A to B car conversions in the coming decades.

An aerospace company builds BART cars

Outbidding Pullman Standard and St. Louis Car Company, the Southern California aerospace manufacturer Rohr Corporation (later Rohr Industries, Inc) was awarded BART contract 2Z4602 – “Procurement of Transit Vehicles.” At $66.7 million, the 150 A cars and 100 B cars were to be among the world’s most expensive rail transit cars. Westinghouse Electric Corp was awarded the subcontract (from Rohr) for the car equipment package of the BART vehicle on July 31, 1969. This package included propulsion equipment, brakes, air conditioning, auxiliary power systems, trucks, and diagnostic test equipment.

Prototype cars

The first 10 cars off of the Rohr assembly line were prototype cars, built to resolve planned and unplanned “bugs” of the new cars during construction and simulated operation, similar to the logic behind prototype commercial aircraft. Legally, the cars were owned by Rohr but operated and maintained by Rohr, its subcontractors, and BART. Between 1970 and 1971, these 10 cars, (7 A-cars #101-107 and 3 B-cars #501-503) were delivered to Hayward shop and began a year-long testing cycle. This was claimed to be among the first examples of a prototype vehicle test program in the industry, and an attempt to avoid the fleet-wide bugs of the Budd Metroliner of the day.

The most striking visual aspect of these prototype cars, in contrast to the production cars, were the liveries. Equipped with a unique teal and blue logo, many A-cars had variation of the livery used today. Their descriptions were as follows:

101: Grey/silver painted cab, Logo. First A car, delivered August 1970

102: White cab, Logo

103: Blue cab, No logo

104: Large numbers (as used today – other cars had smaller numbers on the cab end/Y end), and logo

105: White cab, Logo

106: White cab, no Logo, unpainted feature line (stripes)

107: White cab, Logo

The most striking visual aspect of these prototype cars, in contrast to the production cars, were the liveries. Equipped with a unique teal and blue logo, many A-cars had variation of the livery used today. Their descriptions were as follows:

101: Grey/silver painted cab, Logo. First A car, delivered August 1970

102: White cab, Logo

103: Blue cab, No logo

104: Large numbers (as used today – other cars had smaller numbers on the cab end/Y end), and logo

105: White cab, Logo

106: White cab, no Logo, unpainted feature line (stripes)

107: White cab, Logo

The 103 and 105 lived very short lives – they collided during the morning hours at Coliseum station on November 2, 1971. Afterwards, they were sold and found their way into a local “geodesic dome-BART car house” project, much to the irk of neighbors, and later scrapped. All but A car 107 and the three B cars were scrapped or sold following the prototype car project.

Production cars

The results of the prototype program were followed by the construction of the production cars. Building 61 in the Rohr plant at Chula Vista, CA was the birthplace of over 450 BART cars. Battling waves of problems and controversies, including a strike, an earthquake, train control problems, and other quality control concerns, the first car, A car 108, was accepted in April 1972. The race was on to produce enough cars ready for a September opening day, and the focus was on producing A cars.

Instead of heading straight from Chula Vista to Hayward yard, A car 111 took a brief summer trip to Washington D.C. for display in the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Transpo '72. Rohr’s display included the 111, alongside their proposed car for the DC Metro and Transbus (part of their Flxible bus division).

Instead of heading straight from Chula Vista to Hayward yard, A car 111 took a brief summer trip to Washington D.C. for display in the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Transpo '72. Rohr’s display included the 111, alongside their proposed car for the DC Metro and Transbus (part of their Flxible bus division).

By August 22, 1972, BART received enough cars to begin testing full operations as if it was opening day. Eight trains shuttled between Fremont and MacArthur for three weeks, providing useful experience for all involved.

BART opened its doors to its first revenue riders at Noon on September 11, 1972, following a series of speeches and VIPs rides at 10:00 AM. Throughout the day, nine trains – seven two car trains and two three car trains, carried passengers between MacArthur and Fremont stations.

These short two car trains presented shunting issues, and by October 1972 Rohr prioritized B car production, bringing the end of the “two bagger.”

BART opened its doors to its first revenue riders at Noon on September 11, 1972, following a series of speeches and VIPs rides at 10:00 AM. Throughout the day, nine trains – seven two car trains and two three car trains, carried passengers between MacArthur and Fremont stations.

These short two car trains presented shunting issues, and by October 1972 Rohr prioritized B car production, bringing the end of the “two bagger.”

President Nixon’s ride from San Leandro to Lake Merritt in September 1972 (on A car 120) also provided part of the needed funds for the second order of Rohr cars, which were ordered in the soon after. This order consisted of 100 B cars (fleet numbers 601-700), which were delivered in 1973 and 1974. The third and final order for the A and B cars also totaled 100 cars. This consisted of 26 A cars (fleet numbers 251-276) and 76 B cars (fleet numbers 701-774), which were delivered in 1975. Rohr continued its foray into rail transit cars by producing the WMATA 1000 series cars in an Augusta, GA plant, until the late 1970s.

One of the most famous examples of BART’s troubles was the Fremont Flyer incident on October 2, 1972. The brand new A car 143, with faulty carborne ATC equipment, overshot the southern terminus of the system and landed in the parking lot. The following investigation brought forth major concerns and revisions to the BART ATC system.

Through the 1970s, BART forces battled other major reliability problems with the fleet. A mid-1970s governement report noted that most of the time, as much as half of the fleet was out of service for repairs (and parts shortages), and 1/3 of the trains out in revenue service could not complete the day without a breakdown. The most advanced rapid transit cars in the world required very capable personnel to ensure the system could provide reliable day to day service, no less than a very formidable task.

One of the most famous examples of BART’s troubles was the Fremont Flyer incident on October 2, 1972. The brand new A car 143, with faulty carborne ATC equipment, overshot the southern terminus of the system and landed in the parking lot. The following investigation brought forth major concerns and revisions to the BART ATC system.

Through the 1970s, BART forces battled other major reliability problems with the fleet. A mid-1970s governement report noted that most of the time, as much as half of the fleet was out of service for repairs (and parts shortages), and 1/3 of the trains out in revenue service could not complete the day without a breakdown. The most advanced rapid transit cars in the world required very capable personnel to ensure the system could provide reliable day to day service, no less than a very formidable task.

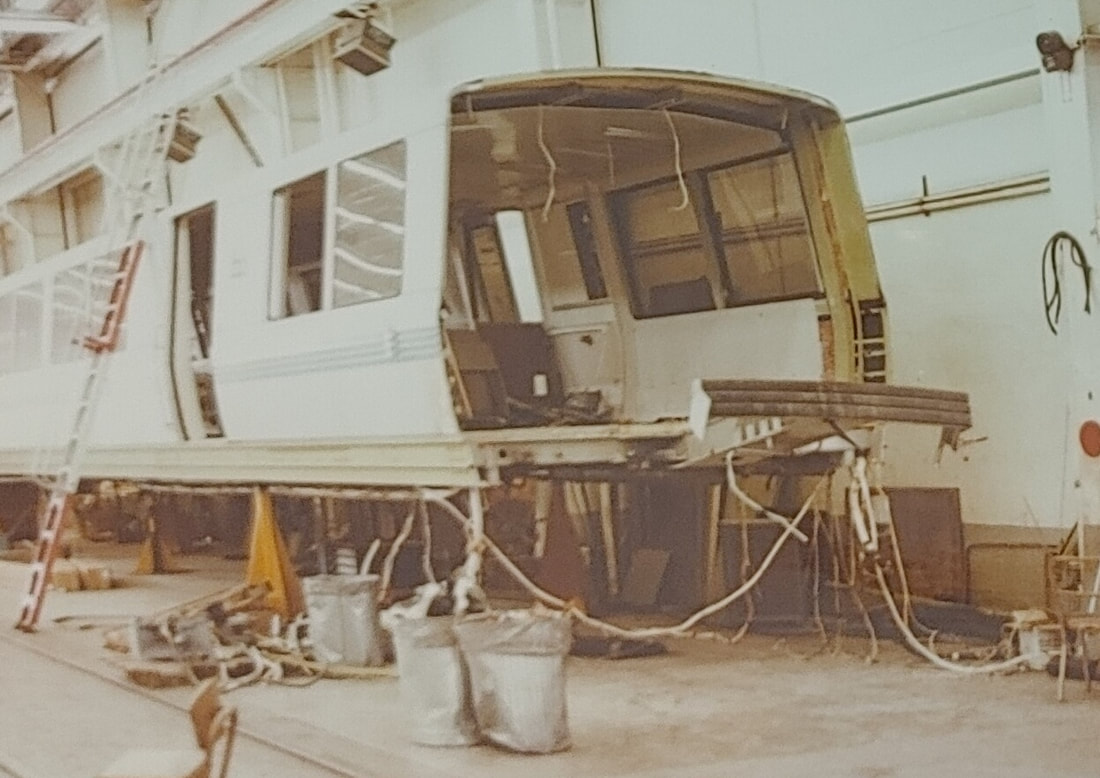

A to B car Program

The early BART revenue fleet orders from Rohr totaled 450 cars. This consisted of 176 A cars and 274 B cars. This was a rather high ratio of A cars to B cars, and time would tell that more B cars would be needed for increased service. Calculations determined that an additional 35 B cars would be needed, but BART forces did not desire another expensive car order nor a four year delivery process.

As a result, a uniquely-BART alternative was considered – cutting off the cabs of A cars, and converting them to B cars. The A car was at an advantage because of the cab consisted of a fiberglass unit mounted to the car, allowing for this one-time conversion (and a trace back to the detachable pod concept explored in the 1960s).

In 1978, work began on converting selected A cars (often with defective and damaged cabs) into B cars. This included the development of jigs to maintain structural integrity of the Y end (former cab end), and rewiring. The initial 35-car project was a success, and throughout BART history, 113 A cars (about 2/3 of the total A car fleet) were converted into B cars. There is no relation between the converted B cars and the original A car number.

As a result, a uniquely-BART alternative was considered – cutting off the cabs of A cars, and converting them to B cars. The A car was at an advantage because of the cab consisted of a fiberglass unit mounted to the car, allowing for this one-time conversion (and a trace back to the detachable pod concept explored in the 1960s).

In 1978, work began on converting selected A cars (often with defective and damaged cabs) into B cars. This included the development of jigs to maintain structural integrity of the Y end (former cab end), and rewiring. The initial 35-car project was a success, and throughout BART history, 113 A cars (about 2/3 of the total A car fleet) were converted into B cars. There is no relation between the converted B cars and the original A car number.

The first car, ex A car 147, renumbered into B car 801 (presently 1801), came online on May 6th, 1978, followed by the second convert, ex A car 137, renumbered into 802 (presently 1802) on September 29, 1978. The Fremont Flyer, A car 143, became B car 826. The last of the original 35 converts rolled out in 1982.

As another benefit, the ATC equipment used in the former A cars was placed into the last order A cars, cars 251-276, which were originally delivered without such equipment (and stored). Oddly enough, the car problems of the 1970s were to the extent that some of these A cars were also stripped of their traction motors to ensure other cars would remain in service. With ATC equipment and motors, the 1975-built A cars entered service. A car 253 was the last Rohr car to be placed into service, on August 8, 1979.

As a footnote, two more A cars (191 and 246) were converted into 800 series B cars in 1993, by Delaware Car works. The 1.8 million dollar conversion and rebuilding process of these cars was used to determine the rebuilding process for the entire Rohr built fleet later in the decade.

As another benefit, the ATC equipment used in the former A cars was placed into the last order A cars, cars 251-276, which were originally delivered without such equipment (and stored). Oddly enough, the car problems of the 1970s were to the extent that some of these A cars were also stripped of their traction motors to ensure other cars would remain in service. With ATC equipment and motors, the 1975-built A cars entered service. A car 253 was the last Rohr car to be placed into service, on August 8, 1979.

As a footnote, two more A cars (191 and 246) were converted into 800 series B cars in 1993, by Delaware Car works. The 1.8 million dollar conversion and rebuilding process of these cars was used to determine the rebuilding process for the entire Rohr built fleet later in the decade.

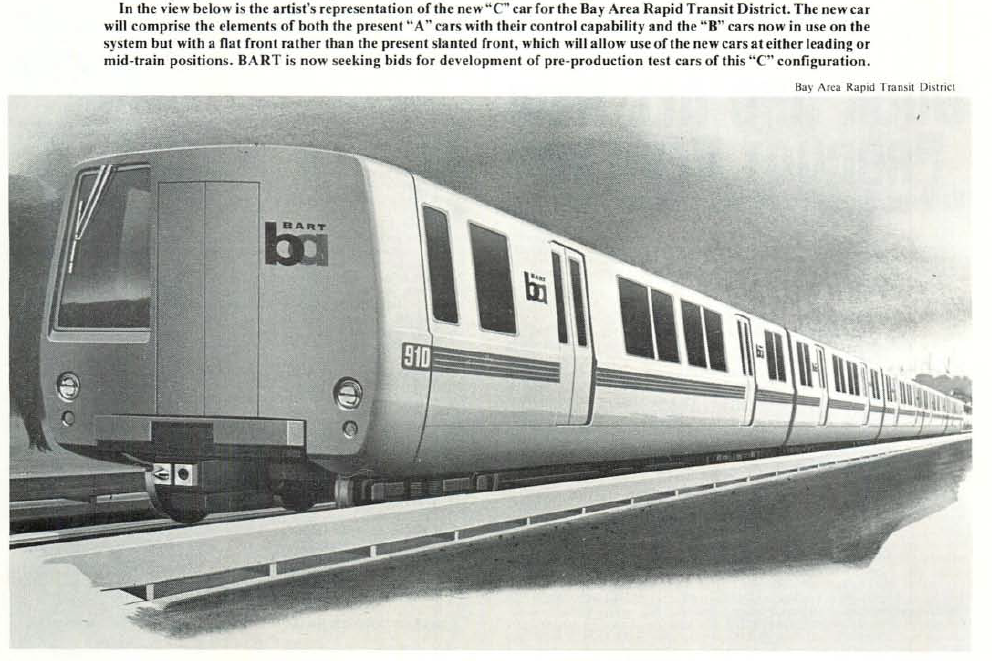

C1 Cars

By the mid-late 1970s, it was apparent that BART needed more B cars, and that BART required more time to change train lengths than desirable. The former problem was addressed with the A to B car conversion program, while the latter required an entirely new car design, the C car.

The C car design allowed for these cars to be used as lead, trailing, or mid-train cars. This contrasted to the original Rohr built fleet of A and B cars, of which were only to be used in lead/trailing and midtrain positions respectively.

C cars allowed for rapid train resizing outside of yards. Traditionally, long trains ran in the commute periods and short trains ran during off peak periods. Before C cars, trains had to return to the yard to add or remove B cars, resulting in additional demands on time and personnel. With C cars, trains can be lengthened (a procedure called a "make") while at the end of the line, and can be shortened by uncoupling 2 C cars, splitting a train into two pieces (a procedure called a "break"). This type of operation allowed for greater flexibility in train sizes.

The contract in October 1982 was originally at $180 Million ($44 million less than the only US Bidder, Budd), At the time, they were the world's most expensive transit units – much to the same as the original A and B cars.

The first 4 C cars, #301-304, were all prototypes used to test/burn-in the C car design, alongside variations in seat layouts. They were built in 1985, in France. After testing, they were scrapped and replaced with production cars of the same fleet number.

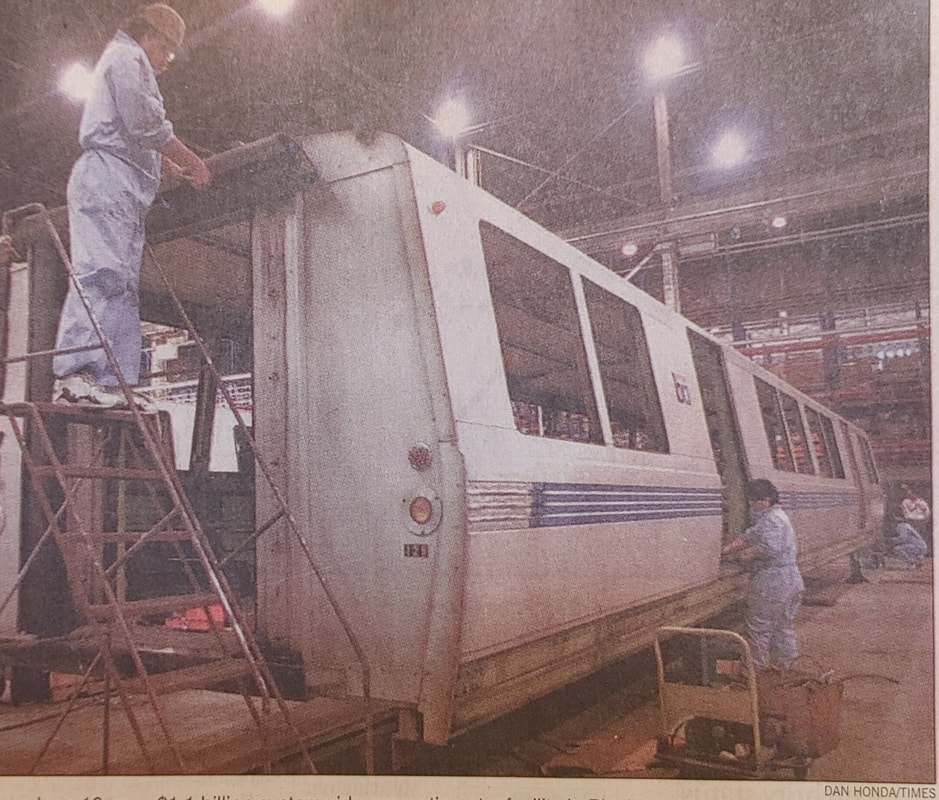

Production cars, replacement #301-304 and #305-450 were assembled between 1987 and 1990 in Union City, CA – a short trip away from their place of delivery at Hayward Yard.

Carbodies were constructed in France, but 2/3 of the car was US made, including Westinghouse traction motors and Knorr dynamic brakes. They retained the characteristic DC traction sounds of BART since its opening.

Before the C2 cars, the C1 cars were originally known as C cars. In later years, the Alstom C1 and Morrison-Knudsen C2 cars were together sometimes regarded as “C cars.” Occasionally though, C1 cars are referred to as "C cars" while the C2s are referred to as "C2 cars."

The C2 cars were the first to go, but the C1 cars have closely followed. As of the time of this writing, less than 50 of them remain in revenue service.

The C car design allowed for these cars to be used as lead, trailing, or mid-train cars. This contrasted to the original Rohr built fleet of A and B cars, of which were only to be used in lead/trailing and midtrain positions respectively.

C cars allowed for rapid train resizing outside of yards. Traditionally, long trains ran in the commute periods and short trains ran during off peak periods. Before C cars, trains had to return to the yard to add or remove B cars, resulting in additional demands on time and personnel. With C cars, trains can be lengthened (a procedure called a "make") while at the end of the line, and can be shortened by uncoupling 2 C cars, splitting a train into two pieces (a procedure called a "break"). This type of operation allowed for greater flexibility in train sizes.

The contract in October 1982 was originally at $180 Million ($44 million less than the only US Bidder, Budd), At the time, they were the world's most expensive transit units – much to the same as the original A and B cars.

The first 4 C cars, #301-304, were all prototypes used to test/burn-in the C car design, alongside variations in seat layouts. They were built in 1985, in France. After testing, they were scrapped and replaced with production cars of the same fleet number.

Production cars, replacement #301-304 and #305-450 were assembled between 1987 and 1990 in Union City, CA – a short trip away from their place of delivery at Hayward Yard.

Carbodies were constructed in France, but 2/3 of the car was US made, including Westinghouse traction motors and Knorr dynamic brakes. They retained the characteristic DC traction sounds of BART since its opening.

Before the C2 cars, the C1 cars were originally known as C cars. In later years, the Alstom C1 and Morrison-Knudsen C2 cars were together sometimes regarded as “C cars.” Occasionally though, C1 cars are referred to as "C cars" while the C2s are referred to as "C2 cars."

The C2 cars were the first to go, but the C1 cars have closely followed. As of the time of this writing, less than 50 of them remain in revenue service.

C2 Cars

The second order C cars, the Morrison-Knudsen-built C2 cars, were ordered in 1992 at a cost of roughly $1.7 million per car (financed locally), and entered revenue service in 1995 and 1996. The car shells were sourced from Germany (and parts from Switzerland), and final assembly was at Hornell, NY (first 5 cars) and Pittsburg, CA (following 75 cars). They were numbered 2501-2580. There were minor differences between the C1 and C2 cars, such as the red ADA lights inside the C2s, lights, seats, and a few details in the cab.

The delivery of these cars helped provide service to the new expansions of the system: Pittsburg/Bay Point (1996), and Dublin/Pleasanton (1997). By the late 2010s, their main home yards were Concord and Hayward, and ran on the Yellow line, Green line, and Blue line, generally speaking.

Reliability problems ushered the end of the C2 cars during the COVID-19 pandemic (with more new cars coming online and reduced service). They were stored, across the system starting around May/June 2020. A train of roughly 8-9 of them was seen testing shortly before the opening of Berryessa and Milpitas, and a few were out in service, briefly, in June 2020. Scrapping wise, 2528 was the first to go in November 2019. All were scrapped by August 2021.

The delivery of these cars helped provide service to the new expansions of the system: Pittsburg/Bay Point (1996), and Dublin/Pleasanton (1997). By the late 2010s, their main home yards were Concord and Hayward, and ran on the Yellow line, Green line, and Blue line, generally speaking.

Reliability problems ushered the end of the C2 cars during the COVID-19 pandemic (with more new cars coming online and reduced service). They were stored, across the system starting around May/June 2020. A train of roughly 8-9 of them was seen testing shortly before the opening of Berryessa and Milpitas, and a few were out in service, briefly, in June 2020. Scrapping wise, 2528 was the first to go in November 2019. All were scrapped by August 2021.

Scrapped cars

Before the scrapping of the first C2 car in 2019, BART lost a few cars due to various incidents:

Car 103 and 105 – Collision under manual control at Coliseum, 11/2/1971

Car 152 – Collision with hi-rail in Oakland, 1/19/1975

Cars 184, 547,* 581, 608, 646, 683 – Transbay Tube fire, 1/17/1979

Car 511 – Mechanical fire, 12/12/1979

Car 676 – Derailment in Oakland Wye, 12/17/1992

*547 damaged and used for fire testing in 1979/1980

Car 103 and 105 – Collision under manual control at Coliseum, 11/2/1971

Car 152 – Collision with hi-rail in Oakland, 1/19/1975

Cars 184, 547,* 581, 608, 646, 683 – Transbay Tube fire, 1/17/1979

Car 511 – Mechanical fire, 12/12/1979

Car 676 – Derailment in Oakland Wye, 12/17/1992

*547 damaged and used for fire testing in 1979/1980

Mid-life Rebuilding

During the turn of the century, as part of a systemwide rehabilitation program, all remaining 439 Rohr A and B cars were rebuilt into A2 and B2 cars.

This rebuilding included the conversion from DC to AC propulsion, new Auxiliary Power Supply Equipment, rebuilt trucks and suspension, a new air compressor, new brake system/hydraulic piping, new battery, new doors, 50% new glass, new carpet, ADA improvements, a cleaned and repaired car body, and new cabs. Many intercar closure doors, many cab doors, glass, trucks, and of course the carbodies were reused for the fleet.

This rebuild, roughly 25-28 years in for the cars, allowed for another quarter century of service from the originally Rohr-built fleet.

The original A cars, (fleet numbers 101-276) were either rebuilt with a cab (and renamed A2 cars, fleet numbers 1164-1276), or rebuilt without a cab (converted into B2 cars, fleet numbers 1838-1913). B cars (fleet numbers 501-774, 801-837) were rebuilt into B2 cars (fleet numbers 1501-1774, 1801-1837).

With the completion of the rebuilding program, it has become common parlance to refer to A2 cars as A cars, and B2 cars as B cars. In all but historical contexts, the terms A and A2 alongside B and B2 are interchangeable.

This rebuilding included the conversion from DC to AC propulsion, new Auxiliary Power Supply Equipment, rebuilt trucks and suspension, a new air compressor, new brake system/hydraulic piping, new battery, new doors, 50% new glass, new carpet, ADA improvements, a cleaned and repaired car body, and new cabs. Many intercar closure doors, many cab doors, glass, trucks, and of course the carbodies were reused for the fleet.

This rebuild, roughly 25-28 years in for the cars, allowed for another quarter century of service from the originally Rohr-built fleet.

The original A cars, (fleet numbers 101-276) were either rebuilt with a cab (and renamed A2 cars, fleet numbers 1164-1276), or rebuilt without a cab (converted into B2 cars, fleet numbers 1838-1913). B cars (fleet numbers 501-774, 801-837) were rebuilt into B2 cars (fleet numbers 1501-1774, 1801-1837).

With the completion of the rebuilding program, it has become common parlance to refer to A2 cars as A cars, and B2 cars as B cars. In all but historical contexts, the terms A and A2 alongside B and B2 are interchangeable.

End of the line

In their rebuilt form, these cars lasted another 20 years in service. As a testament to those that built, rebuilt, maintained, and operated the combined fleet of 669 cars, BART was able to have among the highest rail transit car utilization rates in the country, despite having one of the oldest fleets. Now these cars are being replaced by the new cars, also known as the “Fleet of the Future,” and there is little doubt that these cars will have an interesting history as well.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of BART’s Day One, the first day of revenue service. Almost 400 A2 and B2 cars remain in service today, compared to the total 450 cars ordered in the late 1960s and 1970s, a record for an aluminum-bodied rapid transit car. Soon, only a few will remain, preserved as a reminder of the innovative spirit and half century of service of the original BART cars.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of BART’s Day One, the first day of revenue service. Almost 400 A2 and B2 cars remain in service today, compared to the total 450 cars ordered in the late 1960s and 1970s, a record for an aluminum-bodied rapid transit car. Soon, only a few will remain, preserved as a reminder of the innovative spirit and half century of service of the original BART cars.

All time legacy fleet list

Fleet number Builder/(Rebuilder) Car type Quantity Year/(Rebuilt) Remarks

101-107 Rohr A car 7 1970-1971 Prototype cars

101-276* Rohr A car 174 1971-1975 No 103, 105. 107 ex prototype car

501-503 Rohr B car 3 1970 Prototype cars

504-774 Rohr B car 271 1972-1975

801-837 (OHY/Del car) B car 37 1978-1982/1993 Ex A cars

301-304 Alstom C1 Car 4 1985 Prototype cars

301-450 Alstom C1 car 150 1987-1990

2501-2580 Morrison-Knudsen C2 car 80 1994-1996

1164-1276* (Adtranz/Bombardier) A2 car 59 (2000-2001) Ex A cars

1501-1774* (Adtranz/Bombardier) B2 car 267 (1998-2002) Ex B cars

1801-1913 (Adtranz/Bombardier) B2 car 113 (1998-2002) Ex A and ex B (800s) cars

*Gaps in numbering

101-107 Rohr A car 7 1970-1971 Prototype cars

101-276* Rohr A car 174 1971-1975 No 103, 105. 107 ex prototype car

501-503 Rohr B car 3 1970 Prototype cars

504-774 Rohr B car 271 1972-1975

801-837 (OHY/Del car) B car 37 1978-1982/1993 Ex A cars

301-304 Alstom C1 Car 4 1985 Prototype cars

301-450 Alstom C1 car 150 1987-1990

2501-2580 Morrison-Knudsen C2 car 80 1994-1996

1164-1276* (Adtranz/Bombardier) A2 car 59 (2000-2001) Ex A cars

1501-1774* (Adtranz/Bombardier) B2 car 267 (1998-2002) Ex B cars

1801-1913 (Adtranz/Bombardier) B2 car 113 (1998-2002) Ex A and ex B (800s) cars

*Gaps in numbering

Sources

Dozens of articles, photographs, and reports in the Western Railway Museum Archives.

Lawson, K.L, Chief Equipment Engineer. “Development of the BARTD Vehicle.” Parsons Brinkerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel. May 5, 1966. Western Railway Museum, Bay Area Electric Railway Museum Archives, DB# 177437

Grieg, Michael. “BART’s Dream Car: Luxury Route for Commuters.” June 23, 1965. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library

“Full-Scale Car for BARTD Is Unveiled” Passenger Transport, Volume 23, Number 12, New York, July 2, 1965. Pacific Bus Museum Collection

Demoro, Harre W. “BART’s First Train Ends Work.” Oakland Tribune, December 1, 1971. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library

“National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark.” San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit System

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers International, 1997.

“Train Consist Evaluation and Recommendation” Z949. March, 1967. PBTB

“BART Pact for Motors Awarded.” July 31, 1969. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library

“Noise Reduction is Goal of BART.” June 27, 1971. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library

Demoro, Harre W. “Bugs Delay BART Cars for Test Runs.” June 28, 1971. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library

Demoro, Harre. “Car Supply for BART Debut Full; Tests Start.” Oakland Tribune, August 22, 1972. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library.

“Automatic Train Control in Rail Rapid Transit.” Office of Technology Assessment. May 1976.

"Turning A's into B's a Success: The Saga of the Fremont Flyer: Epilogue." BARTalk, November 1981

Demoro, Harre. “Out West” Pacific News, February 1980.

Kristopans, Andre. "Modern Urban Rail Systems." October 2019

Lawson, K.L, Chief Equipment Engineer. “Development of the BARTD Vehicle.” Parsons Brinkerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel. May 5, 1966. Western Railway Museum, Bay Area Electric Railway Museum Archives, DB# 177437

Grieg, Michael. “BART’s Dream Car: Luxury Route for Commuters.” June 23, 1965. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library

“Full-Scale Car for BARTD Is Unveiled” Passenger Transport, Volume 23, Number 12, New York, July 2, 1965. Pacific Bus Museum Collection

Demoro, Harre W. “BART’s First Train Ends Work.” Oakland Tribune, December 1, 1971. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library

“National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark.” San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit System

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers International, 1997.

“Train Consist Evaluation and Recommendation” Z949. March, 1967. PBTB

“BART Pact for Motors Awarded.” July 31, 1969. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library

“Noise Reduction is Goal of BART.” June 27, 1971. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library

Demoro, Harre W. “Bugs Delay BART Cars for Test Runs.” June 28, 1971. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library

Demoro, Harre. “Car Supply for BART Debut Full; Tests Start.” Oakland Tribune, August 22, 1972. Collection of: BARTD General Rolling Stock News, Norman Therkelson Collection, Prelinger Library.

“Automatic Train Control in Rail Rapid Transit.” Office of Technology Assessment. May 1976.

"Turning A's into B's a Success: The Saga of the Fremont Flyer: Epilogue." BARTalk, November 1981

Demoro, Harre. “Out West” Pacific News, February 1980.

Kristopans, Andre. "Modern Urban Rail Systems." October 2019

Last Updated: 1/28/2023 ATP, 9/16/23