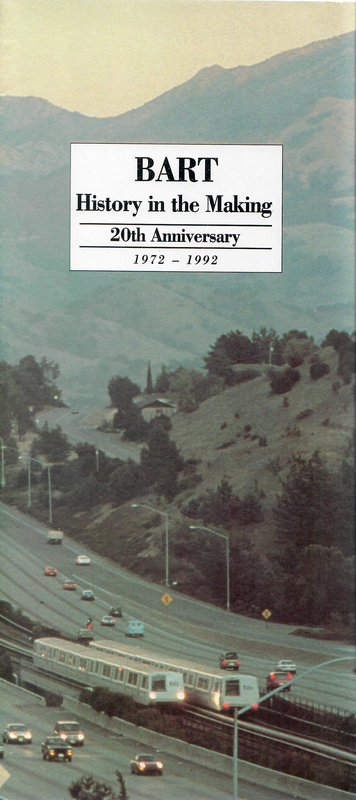

BART

History in the Making

20th Anniversary

1972-1992

Digitized in 2022

Vision To Reality:

A Transit Renaissance

Early Beginnings

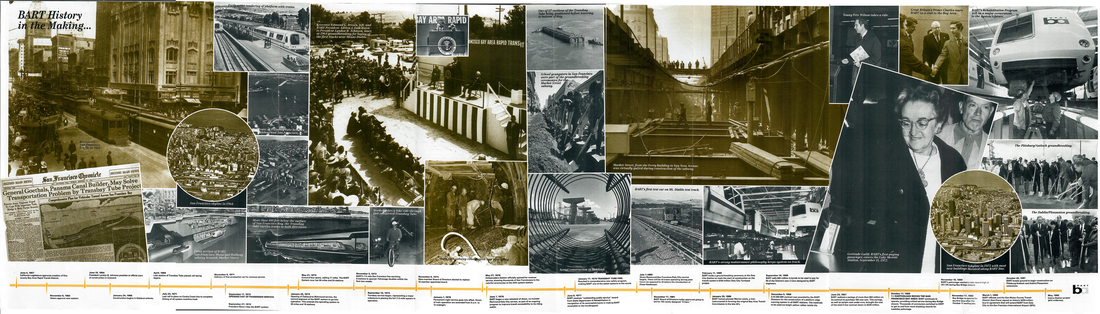

Even before the end of the Second World War, community, governmental and military officials were concerned about the postwar transportation scene in the San Francisco Bay Area.

A joint Army-Navy Board of Enquiry had already considered the desirability of an Alameda-San Francisco bridge from “a national defense viewpoint.” In 1941, this board had recommended against its construction. In 1943, the same Army-Navy Board was reactivated and told to take another look at the need and feasibility of an additional Bay crossing.

After considering nearly two dozen possible plans and holding public hearings, the Joint Board in 1947 called for a high-speed electric train system to serve both sides of the Bay, with a tube under the Bay between Oakland and San Francisco.

Even before the end of the Second World War, community, governmental and military officials were concerned about the postwar transportation scene in the San Francisco Bay Area.

A joint Army-Navy Board of Enquiry had already considered the desirability of an Alameda-San Francisco bridge from “a national defense viewpoint.” In 1941, this board had recommended against its construction. In 1943, the same Army-Navy Board was reactivated and told to take another look at the need and feasibility of an additional Bay crossing.

After considering nearly two dozen possible plans and holding public hearings, the Joint Board in 1947 called for a high-speed electric train system to serve both sides of the Bay, with a tube under the Bay between Oakland and San Francisco.

Legislature Lends A Hand

Then in 1949, the California Legislature passed a bill authorizing the formation of a regional district in the Bay Area to provide rapid transit facilities.

Study Proposed

In 1951, the Legislature approved an amendment to the original 1949 enabling legislation. The amendment created the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission and appropriated $50,000-approximately $200,000 today—for the Commission to "study and investigate the rapid transit problems in the San Francisco Bay Area."

In 1957 the transit commission made its recommendation to the Legislature.

State Creates BART

On June 4, 1957, the Legislature approved the creation of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District, consisting of Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo counties. Santa Clara County was included in the early stages of the legislation, but at the request of county officials, it was dropped from the final bill.

By the summer of 1961, the final engineering plan, completed by PBTB and approved by BART Directors, was ready for submission to the supervisors of the five District counties.

San Mateo County supervisors were cool to the plan, and in December, 1961, they pulled the County out of the District altogether. With the District-wide tax base now reduced, Marin County supervisors followed suit and pulled their County out early in 1962.

So the PBTB planners went back to the drawing boards and prepared a fifth plan for a system in the remaining three counties. This final plan was completed in the spring of 1962. It was approved by BART and submitted to the county supervisors.

The proposed system was now reduced to approximately 71.5 miles of double track, linking the west and east sides of the Bay through the Transbay Tube, 31 miles of aerial construction and 24 miles of construction at grade. The underground portion included about 11 miles of subway, five miles of tunnels and the four miles of subaqueous tube.

The plan called for a $792 million general obligation bond issue to pay for basic construction, excluding the tube and transit cars. (The Tube now was to be financed and built by the California Toll Bridge Authority and BART intended to pay for the passenger cars by the issuance of revenue bonds.)

Then in 1949, the California Legislature passed a bill authorizing the formation of a regional district in the Bay Area to provide rapid transit facilities.

Study Proposed

In 1951, the Legislature approved an amendment to the original 1949 enabling legislation. The amendment created the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission and appropriated $50,000-approximately $200,000 today—for the Commission to "study and investigate the rapid transit problems in the San Francisco Bay Area."

In 1957 the transit commission made its recommendation to the Legislature.

State Creates BART

On June 4, 1957, the Legislature approved the creation of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District, consisting of Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo counties. Santa Clara County was included in the early stages of the legislation, but at the request of county officials, it was dropped from the final bill.

By the summer of 1961, the final engineering plan, completed by PBTB and approved by BART Directors, was ready for submission to the supervisors of the five District counties.

San Mateo County supervisors were cool to the plan, and in December, 1961, they pulled the County out of the District altogether. With the District-wide tax base now reduced, Marin County supervisors followed suit and pulled their County out early in 1962.

So the PBTB planners went back to the drawing boards and prepared a fifth plan for a system in the remaining three counties. This final plan was completed in the spring of 1962. It was approved by BART and submitted to the county supervisors.

The proposed system was now reduced to approximately 71.5 miles of double track, linking the west and east sides of the Bay through the Transbay Tube, 31 miles of aerial construction and 24 miles of construction at grade. The underground portion included about 11 miles of subway, five miles of tunnels and the four miles of subaqueous tube.

The plan called for a $792 million general obligation bond issue to pay for basic construction, excluding the tube and transit cars. (The Tube now was to be financed and built by the California Toll Bridge Authority and BART intended to pay for the passenger cars by the issuance of revenue bonds.)

Joseph Silva Makes A Difference

Supervisors in Alameda and San Francisco counties approved the plan and slated the issuance of $792 million in general obligation bonds for the November ballot. The plan was due to be voted on by the five-member Board of Supervisors of Contra Costa County in July. If the Contra Costa supervisors didn't vote to put the bond issue on the November ballot, the whole project could be forgotten. Losing San Mateo and Marin counties was bad enough, but without Contra Costa County's potential tax participation, a truncated two-county system wasn't feasible.

Four of the Contra Costa supervisors had already gone on record: two were for the plan, two were against. The deciding vote belonged to Supervisor Joseph S. Silva, a farmer from the County's northeastern corner.

Supervisors in Alameda and San Francisco counties approved the plan and slated the issuance of $792 million in general obligation bonds for the November ballot. The plan was due to be voted on by the five-member Board of Supervisors of Contra Costa County in July. If the Contra Costa supervisors didn't vote to put the bond issue on the November ballot, the whole project could be forgotten. Losing San Mateo and Marin counties was bad enough, but without Contra Costa County's potential tax participation, a truncated two-county system wasn't feasible.

Four of the Contra Costa supervisors had already gone on record: two were for the plan, two were against. The deciding vote belonged to Supervisor Joseph S. Silva, a farmer from the County's northeastern corner.

|

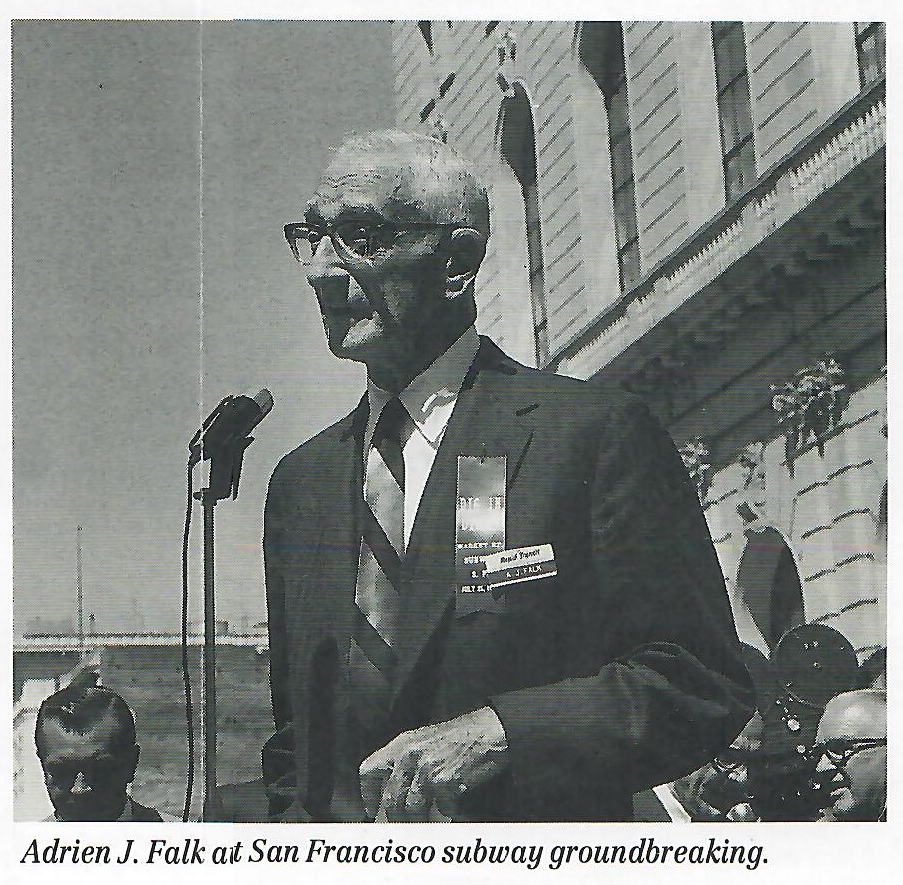

George Christopher, who was San Francisco's Mayor at the time, along with Oakland's Mayor, John Houlihan, plus Adrien J. Falk, President of the District's Board of Directors, drove to Martinez to talk to Silva on the morning of the day set for the Contra Costa vote. Houlihan thought it was a waste of time. He figured that Silva wouldn't approve the plan because of the disapproval of his former constituents: “Silva was a 'no' vote in my book," Houlihan later recalled. Christopher, Houlihan and Falk met Silva at a small doughnut and coffee shop on Alhambra Avenue early in the morning. “There wasn't a single table in the place. All counter, Christopher recalled. “Joe, how can we meet here?” Christopher asked Silva. “We'll meet here at the counter," Silva replied.

|

And so the four men sat down on stools at the counter and talked about the rapid transit proposal and the crucial vote set for the afternoon. The three visitors took turns talking to Silva, but they couldn't get any kind of sign from Silva that he was going to vote to put the bond issue on the ballot. “We hammered away at him, but he wouldn't budge,” Christopher recalled. Houlihan was disgusted. He leaned over to Christopher and whispered, “Tell him to go to hell, George, and let's get out of here." But the Mayor of San Francisco was not yet daunted. He turned again to Silva: “Look, Joe, this rapid transit thing is going to happen some day, sooner or later, no matter how you vote this afternoon. The only question is when it's going to happen. I know it's going to cost a lot of money, but it's going to happen. Just vote this afternoon to get the bonds on the ballot. If the voters don't want the bonds, okay, that's their decision, but give them the chance to decide. I think the voters are going to approve the plan. I think we're going to have a great transit system. You'll be known as the man who made it possible. You'll have the deciding vote. Joe Silva of Contra Costa County. Just think about that, Joe.”

Before the conversation ended, so the story goes, the phone rang and it was Governor Pat Brown calling Joe at the doughnut shop to add to the weight of the others. “The Bay Area needs this transit system, Joe,” the governor was reported to have said.

When Christopher, Falk and Houlihan left the coffee shop, they still didn't know just how Silva was going to vote. The independent-minded farmer from Brentwood kept his counsel to the last. But when the rapid transit plan came up for a vote that afternoon, Joseph S. Silva voted “aye.”

Vote Says 'Go? Then ...

On November 6, 1962, almost three-quarters of a million voters in the three counties voted on the question of issuing $792 million in bonds to build the rapid transit system. The 'yes' votes represented 61.215 percent of the total, a narrow but definite margin above the 60 percent required to authorize the bonds.

In Contra Costa County, the bond issue did not receive a 60 percent 'yes' vote, but since the votes from the three counties were lumped together, the bond issue passed—just! In Alameda County the 'yes' vote was 60.039 percent, about as close as you can get, but In San Francisco the favorable vote was 66.888 percent, overriding the smaller 'yes' tallies in the other two counties. Yet even in Costa County the 'yes' vote reached 54.5 percent, showing that a majority of the county voters approved the plan and the issuance of the bonds.

Three weeks after the election, four District voters filed a suit in State Superior Court in Martinez. They charged that the voters had not been given sufficient facts about the project, that the fees to be paid under the final engineering contract were excessive and that the contract itself was not properly awarded to PBTB by the District's Directors.

However, in May 1963, Judge Martin E. Rothenberg disposed of all legal challenges, freeing the District to move forward with its plan.

On November 6, 1962, almost three-quarters of a million voters in the three counties voted on the question of issuing $792 million in bonds to build the rapid transit system. The 'yes' votes represented 61.215 percent of the total, a narrow but definite margin above the 60 percent required to authorize the bonds.

In Contra Costa County, the bond issue did not receive a 60 percent 'yes' vote, but since the votes from the three counties were lumped together, the bond issue passed—just! In Alameda County the 'yes' vote was 60.039 percent, about as close as you can get, but In San Francisco the favorable vote was 66.888 percent, overriding the smaller 'yes' tallies in the other two counties. Yet even in Costa County the 'yes' vote reached 54.5 percent, showing that a majority of the county voters approved the plan and the issuance of the bonds.

Three weeks after the election, four District voters filed a suit in State Superior Court in Martinez. They charged that the voters had not been given sufficient facts about the project, that the fees to be paid under the final engineering contract were excessive and that the contract itself was not properly awarded to PBTB by the District's Directors.

However, in May 1963, Judge Martin E. Rothenberg disposed of all legal challenges, freeing the District to move forward with its plan.

|

Bart Breaks Ground

The official date for the start of construction was June 19, 1964, with President Lyndon B. Johnson presiding at a groundbreaking for the laying of 4.4 miles of track between Concord and Walnut Creek. The Heart of BART The heart of BART lies in a tube in a trench, 135 feet below the surface of San Francisco Bay at its deepest point. The Transbay Tube is not only an engineering achievement. It symbolizes the very essence of the BART concept. The concept of an under-the-Bay tube had been around for many years. In October, 1920, Major General George T. Goethals, the builder of the Panama Canal, made public his proposal for building such a tube "in order to solve the acute transportation problems facing San Francisco and East Bay communities." Goethals' proposal envisioned a two-level tube to accommodate automobiles, trucks and trains. The alignment of Goethals' proposed tube is almost exactly the same as the alignment taken by BART's Transbay Tube. |

The Tube consists of 57 steel and concrete sections, constructed on the west side of the Bay and floated to a spot above their designated position on the floor of the Bay. The sections were lowered into place into a trench, 70 to 100 feet deep, which was dredged out of the Bay bottom between Oakland and San Francisco. The first section was placed in position in February, 1967, and the last in April, 1969.

The Transbay Tube cost $180 million, every dime coming from automobile tolls on State bridges crossing the Bay.

New Costs

In 1966, the District's Directors knew that they would not have enough money to complete the system as designed in 1962 and later modified to meet the requirements of local communities.

In April, 1969, after three years of consideration, the Legislature granted the District's request for $150 million by authorizing the levy of a halfcent sales tax in the BART counties. BART was able to issue bonds against the projected sales-tax revenues.

At the same time, federal funds began to be available for the project.

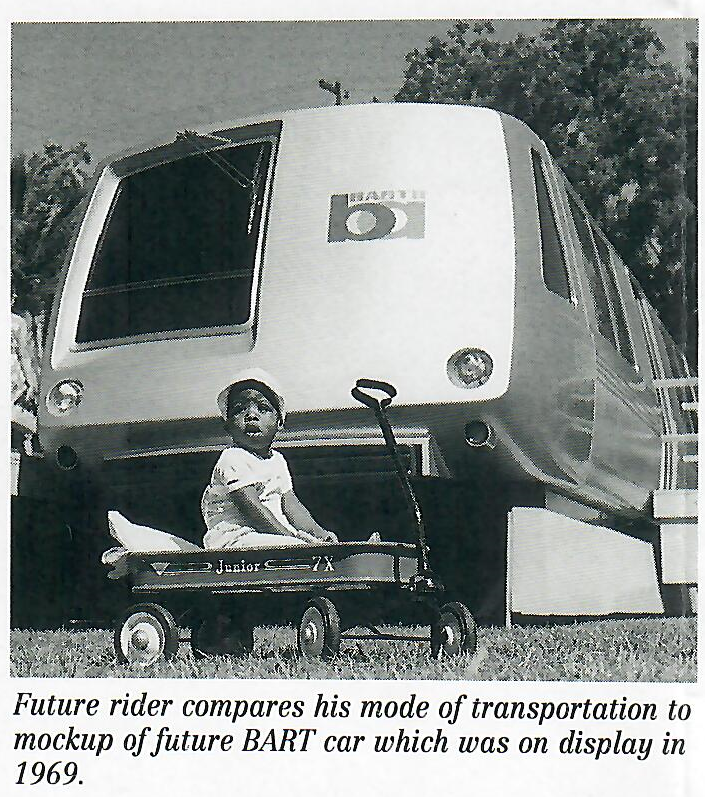

Of the $160 million base cost of BART's 450-car fleet, 64 percent was eventually funded by federal grants. The first prototype car was delivered in August, 1970. The car's manufacturer, saddled with a nine-week strike and other delays, fell a full year behind in its delivery schedule.

The Transbay Tube cost $180 million, every dime coming from automobile tolls on State bridges crossing the Bay.

New Costs

In 1966, the District's Directors knew that they would not have enough money to complete the system as designed in 1962 and later modified to meet the requirements of local communities.

In April, 1969, after three years of consideration, the Legislature granted the District's request for $150 million by authorizing the levy of a halfcent sales tax in the BART counties. BART was able to issue bonds against the projected sales-tax revenues.

At the same time, federal funds began to be available for the project.

Of the $160 million base cost of BART's 450-car fleet, 64 percent was eventually funded by federal grants. The first prototype car was delivered in August, 1970. The car's manufacturer, saddled with a nine-week strike and other delays, fell a full year behind in its delivery schedule.

|

Opening Day September 11, 1972 was a great day in the history of the Bay Area as BART first opened the doors for service of the nation's shiny new transit system. The public had already had glimpses of the system during its development, the award-winning architecture of its stations, the linear park along portions of its aerial rights-of-way, works of art commissioned to bring a certain richness to the system's interiors, and the Buck Rogers look to the transit cars. This was the beginning of a new era, a renaissance in rail rapid transit. And now, at last, after a long rocky road to completion, it was ready to be unveiled and put into service. It was an exciting time. |

Now, on this warm, sunny day in September large crowds gathered at BART's Lake Merritt Station in Oakland, and at 11 other stations along 26 miles of track from Fremont in southern Alameda County to MacArthur Station in North Oakland. The crowds were there to ride the new system, and to hear opening day speeches from various dignitaries who had traveled from near and far to be on hand for the new system's launching.

At precisely 12 noon, following the ceremonies, BART's General Manager at the time, B. R. Stokes declared the system open and eight two-car trains began circulating along the line. Gertrude Guild, of Oakland, then inserted her ticket into the automatic fare gate at the Lake Merritt Station and walked through into the station to become a part of BART's history as its very first paying passenger. By the end of the first week, the system had carried 100,000 passengers.

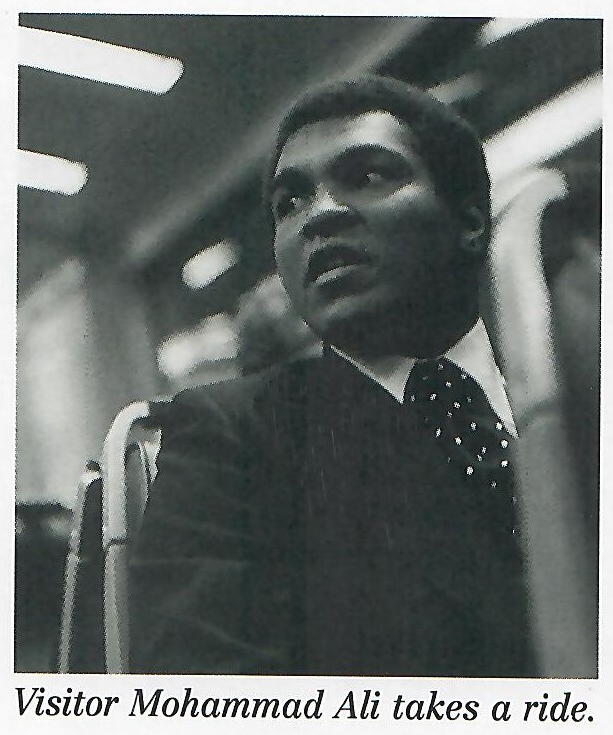

Whole World Is Watching

BART's initial run that September morning was not just a local event. Members of the media from across the nation and around the world were on hand with local journalists to witness and record the occasion. One local newspaper summed it all up with a cartoon which showed BART peaking out sheepishly from behind a curtain. The captain read: The Whole World Is Watching. And so it was. After all, BART was the first all-new rail rapid transit system to be built in the United States in almost 60 years. It was in effect a new pioneer in ground transportation. And it would serve as the model for future new systems, such as those in Washington, D.C. and Atlanta, Georgia.

President Rides Train

On September 27, President Richard Nixon took a ride on the new system, praising it highly as paving the way to the future. He also announced a $27 million grant to help purchase additional cars. BART's initial order from Rohr Corporation, the builder of the first BART cars, was for only 250 vehicles. BART ordered 200 more while cars from the first order were still coming off the assembly line.

In January, 1973, the Richmond line was opened, the Concord line in May, 1973, the intra San Francisco Service from Montgomery to Daly City in November, 1973. Now BART had 33 stations open. But, everything wasn't smooth sailing for the fledgling system, to say the least. The September opening date had been moved back twice during 1971 and 1972, and even getting the trains into operation on September 11 required a maximum effort from BART's engineers and staff. Then on October 2, a train went off the end of the track at the Fremont Station and into the parking lot, setting off a public clamor for investigations and fixes.

Technical Problems

Due to the technical problems the system had had from its opening day, transbay services could not begin until September 16, 1974 after the California Public Utilities Commission, BART's safety regulatory agency, gave the okay—and only after the safety of the operation was clearly demonstrated.

Another major milestone was reached with the opening of the 34th station, the station that was not part of the original plan—the Embarcadero Station, one of the busiest stations on the system today. It was an afterthought, paid for by the local business community, redevelopment money, and some money from HUD. It is hard today to imagine BART without the Embarcadero Station.

Over the next seven years a great effort was put forth to correct the technical glitches. Gradually, after many modifications to the equipment, the system was performing well and ready to move ahead with further improvements. However, on January 17, 1979 a train fire in the transbay tube changed BART forever. It resulted in BART assessing its overall safety program, and replacing the seats, the interior walls and floors of the cars, and making numerous modifications to the plan and facilities. BART invested over $40 million in the program. But when the major modifications were completed, BART's worst critics were calling the system the safest in the world today.

In 1980 BART reached another milestone when it finally opened the long-awaited direct service between Richmond and San Francisco/Daly City which in fact was the introduction of close headways (running trains closer together). That is, BART had solved many of its early technical problems that now allowed it to operate trains at less than one station apart instead of no less than one station apart as had been the case.

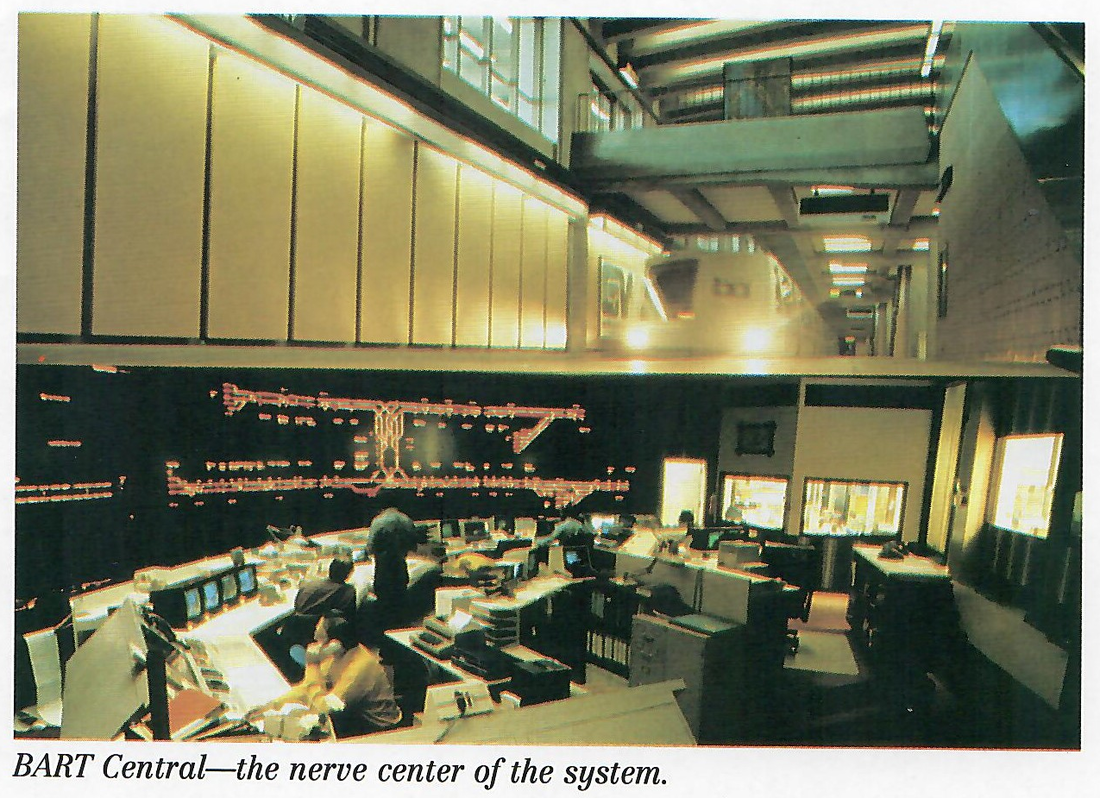

Second Generation: New Transit Cars

Throughout the new decade, BART made strides to improve. New transit cars were purchased with a brand new look, and a double function. These were called the C cars and could be used as both a lead car or a mid-train car, unlike the original fleet which had two different cars —the A, with the slant nose, and the B which would serve as a mid-train car. Also, a new track through downtown Oakland was constructed, a turn-back track at Daly City, which would be critical to further improvements to train frequency, a new computer system, and several other capital investments.

BART's initial run that September morning was not just a local event. Members of the media from across the nation and around the world were on hand with local journalists to witness and record the occasion. One local newspaper summed it all up with a cartoon which showed BART peaking out sheepishly from behind a curtain. The captain read: The Whole World Is Watching. And so it was. After all, BART was the first all-new rail rapid transit system to be built in the United States in almost 60 years. It was in effect a new pioneer in ground transportation. And it would serve as the model for future new systems, such as those in Washington, D.C. and Atlanta, Georgia.

President Rides Train

On September 27, President Richard Nixon took a ride on the new system, praising it highly as paving the way to the future. He also announced a $27 million grant to help purchase additional cars. BART's initial order from Rohr Corporation, the builder of the first BART cars, was for only 250 vehicles. BART ordered 200 more while cars from the first order were still coming off the assembly line.

In January, 1973, the Richmond line was opened, the Concord line in May, 1973, the intra San Francisco Service from Montgomery to Daly City in November, 1973. Now BART had 33 stations open. But, everything wasn't smooth sailing for the fledgling system, to say the least. The September opening date had been moved back twice during 1971 and 1972, and even getting the trains into operation on September 11 required a maximum effort from BART's engineers and staff. Then on October 2, a train went off the end of the track at the Fremont Station and into the parking lot, setting off a public clamor for investigations and fixes.

Technical Problems

Due to the technical problems the system had had from its opening day, transbay services could not begin until September 16, 1974 after the California Public Utilities Commission, BART's safety regulatory agency, gave the okay—and only after the safety of the operation was clearly demonstrated.

Another major milestone was reached with the opening of the 34th station, the station that was not part of the original plan—the Embarcadero Station, one of the busiest stations on the system today. It was an afterthought, paid for by the local business community, redevelopment money, and some money from HUD. It is hard today to imagine BART without the Embarcadero Station.

Over the next seven years a great effort was put forth to correct the technical glitches. Gradually, after many modifications to the equipment, the system was performing well and ready to move ahead with further improvements. However, on January 17, 1979 a train fire in the transbay tube changed BART forever. It resulted in BART assessing its overall safety program, and replacing the seats, the interior walls and floors of the cars, and making numerous modifications to the plan and facilities. BART invested over $40 million in the program. But when the major modifications were completed, BART's worst critics were calling the system the safest in the world today.

In 1980 BART reached another milestone when it finally opened the long-awaited direct service between Richmond and San Francisco/Daly City which in fact was the introduction of close headways (running trains closer together). That is, BART had solved many of its early technical problems that now allowed it to operate trains at less than one station apart instead of no less than one station apart as had been the case.

Second Generation: New Transit Cars

Throughout the new decade, BART made strides to improve. New transit cars were purchased with a brand new look, and a double function. These were called the C cars and could be used as both a lead car or a mid-train car, unlike the original fleet which had two different cars —the A, with the slant nose, and the B which would serve as a mid-train car. Also, a new track through downtown Oakland was constructed, a turn-back track at Daly City, which would be critical to further improvements to train frequency, a new computer system, and several other capital investments.

|

BART Shines

It wasn't until October 17, 1989 that BART truly showed the world what it was made of. At 5:04 in the afternoon the Loma Prieta earthquake put BART to the test and the system came through with flying colors. The Bay Bridge had lost a section and was closed down, the Cypress freeway had collapsed, and Highway 280 in San Francisco was closed, along with the Embarcadero Freeway. For core Bay Area commuters going between east and west bay, BART was the only game in town. Ridership went from 219,000 a day to a peak of 357,000 a day. But the system performed and so did the system's employees. When asked by a member of the media if the system could handle it, BART's new General Manager Frank J. Wilson said, “We're going to put everything out there that we can and run the wheels off it, if that's what it takes." As one national newspaper put it, it was “BART's Shining Hour." |

It was also the beginning of a new era for BART. Many of the new riders stayed with BART after the bridge opened, and the people of the Bay Area saw that the investment they had made in their transit system was a very good one.

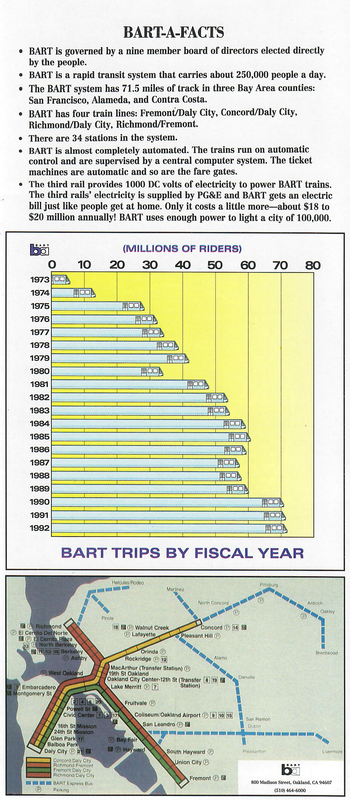

BART today carries about 250,000 passengers a day, operating 43 trains during peak periods. Since first opening, the system has carried about one billion passengers over 12 billion passenger miles with one of the best safety records in the world.

BART today carries about 250,000 passengers a day, operating 43 trains during peak periods. Since first opening, the system has carried about one billion passengers over 12 billion passenger miles with one of the best safety records in the world.

|

BART Builds For The Future

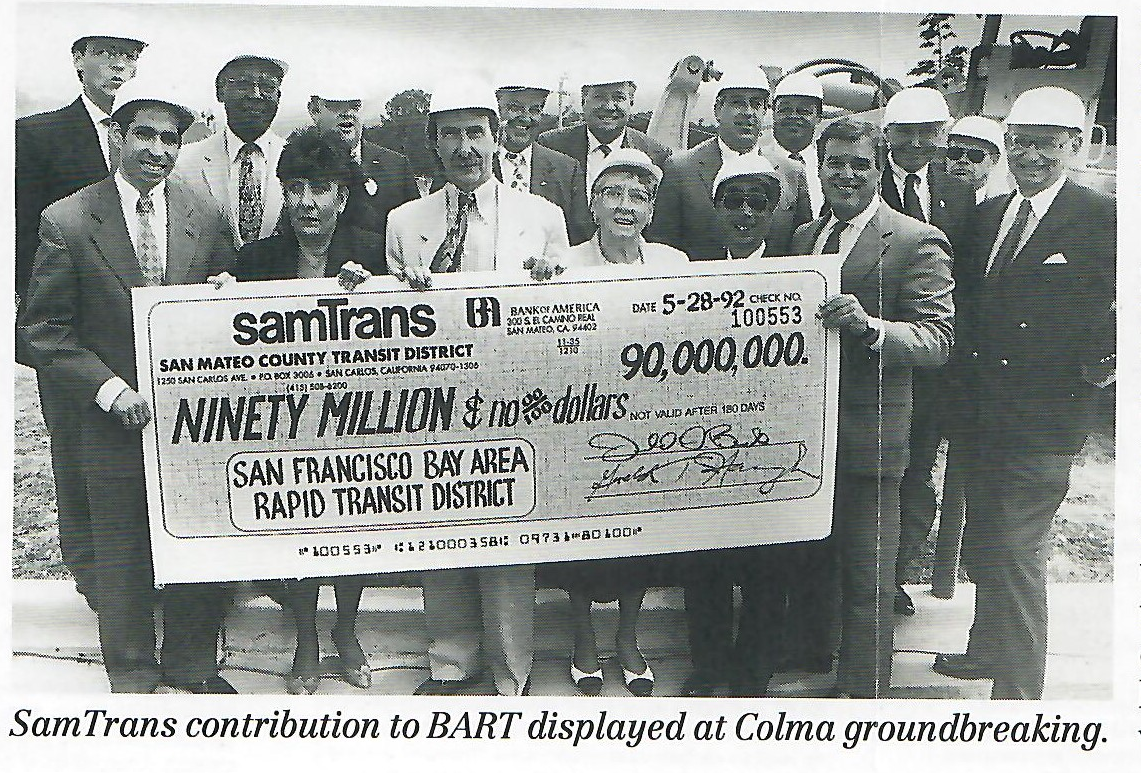

BART is embarked on a $2.6 billion program to extend its services to communities in Alameda, Contra Costa and San Mateo counties. This ambitious project is the largest construction undertaking at BART since the system was built. During the 1990s and into the new century, the first phase, consisting of four separate extensions of this ambitious program will add almost 34 miles of new double track and a minimum of 10 new stations. Actual construction began in 1991 on the North Concord/West Pittsburg and the Dublin/Pleasanton extensions and in 1992 on the Colma extension. |

The North Concord/West Pittsburg extension will run north from the existing Concord Station to a North Concord/Martinez Station and then east to a West Pittsburg Station. Construction is expected to be completed in 1997. This extension, with 8.7 miles of track and two stations, is estimated to cost $506 million. BART is studying the possibility of being able to take this extension beyond West Pittsburg within the estimated costs.

The Dublin/Pleasanton extension will run east from the existing Bayfair Station in San Leandro. It provides for a station in Castro Valley, a second station at West Dublin/Pleasanton and, if additional funds become available, a third station at East Dublin/Pleasanton.

Construction is expected to be completed by late 1995. The twostation project is estimated to cost $517 million.

The Warm Springs extension will run south from the existing Fremont Station and will include an Irvington Station and a Warm Springs Station. A South Warm Springs Station will be considered at a later date.

Completion of the project is expected in early 1998. The two-station project is estimated to cost $540 million.

The Colma Station is the first station on the extension south from the existing Daly City Station to a station providing access to the San Francisco International Airport. Completion is anticipated by late 1995. The estimated price tag is $139 million.

From Colma, the airport extension will proceed to Chester Avenue in South San Francisco, then continue to a location near the Tanforan Shopping Center in San Bruno. The extension will end at a station in the vicinity of the airport. Construction of the three stations south of Colma is expected to be completed in 2000. Their cost is estimated at $540 million.

The estimated $2.6 billion to pay for BART's first-phase extensions comes from a variety of sources, including sales tax receipts, bridge tolls, state grants, federal grants and BART capital resources, as well as a $200 million contribution from the San Mateo County Transit District. The SamTrans contribution is specifically earmarked to pay for extensions in the East Bay.

The District estimates that, over the entire project, a total of 147,000 jobs will be created and that thousands of opportunities will be afforded to local businesses and manufacturers to keep the project supplied.

Rehabilitation-A Cornerstone of the Future

The District has launched a program aimed at restoring and modernizing its basic infrastructure and rolling stock.

The program can be summed up by the old saying, “A stitch in time saves nine.” The program, by restoring basic structures and equipment now, before they are subject to additional wear and tear, will prolong their productive life beyond their original expectations The program represents basic prudence.

The estimated cost of the rehabilitation amounts to $820 million. Most of the work is scheduled to be completed by the year 2000 and includes these major components: passenger vehicles which have logged over a million miles each, $350 million; control and communications, $80 million; automatic fare collectors, $50 million; maintenance vehicles and equipment, $10 million; stations and mainline, $50 million; maintenance facilities, $50 million; and power, $230 million.

The Dublin/Pleasanton extension will run east from the existing Bayfair Station in San Leandro. It provides for a station in Castro Valley, a second station at West Dublin/Pleasanton and, if additional funds become available, a third station at East Dublin/Pleasanton.

Construction is expected to be completed by late 1995. The twostation project is estimated to cost $517 million.

The Warm Springs extension will run south from the existing Fremont Station and will include an Irvington Station and a Warm Springs Station. A South Warm Springs Station will be considered at a later date.

Completion of the project is expected in early 1998. The two-station project is estimated to cost $540 million.

The Colma Station is the first station on the extension south from the existing Daly City Station to a station providing access to the San Francisco International Airport. Completion is anticipated by late 1995. The estimated price tag is $139 million.

From Colma, the airport extension will proceed to Chester Avenue in South San Francisco, then continue to a location near the Tanforan Shopping Center in San Bruno. The extension will end at a station in the vicinity of the airport. Construction of the three stations south of Colma is expected to be completed in 2000. Their cost is estimated at $540 million.

The estimated $2.6 billion to pay for BART's first-phase extensions comes from a variety of sources, including sales tax receipts, bridge tolls, state grants, federal grants and BART capital resources, as well as a $200 million contribution from the San Mateo County Transit District. The SamTrans contribution is specifically earmarked to pay for extensions in the East Bay.

The District estimates that, over the entire project, a total of 147,000 jobs will be created and that thousands of opportunities will be afforded to local businesses and manufacturers to keep the project supplied.

Rehabilitation-A Cornerstone of the Future

The District has launched a program aimed at restoring and modernizing its basic infrastructure and rolling stock.

The program can be summed up by the old saying, “A stitch in time saves nine.” The program, by restoring basic structures and equipment now, before they are subject to additional wear and tear, will prolong their productive life beyond their original expectations The program represents basic prudence.

The estimated cost of the rehabilitation amounts to $820 million. Most of the work is scheduled to be completed by the year 2000 and includes these major components: passenger vehicles which have logged over a million miles each, $350 million; control and communications, $80 million; automatic fare collectors, $50 million; maintenance vehicles and equipment, $10 million; stations and mainline, $50 million; maintenance facilities, $50 million; and power, $230 million.

5/5/21